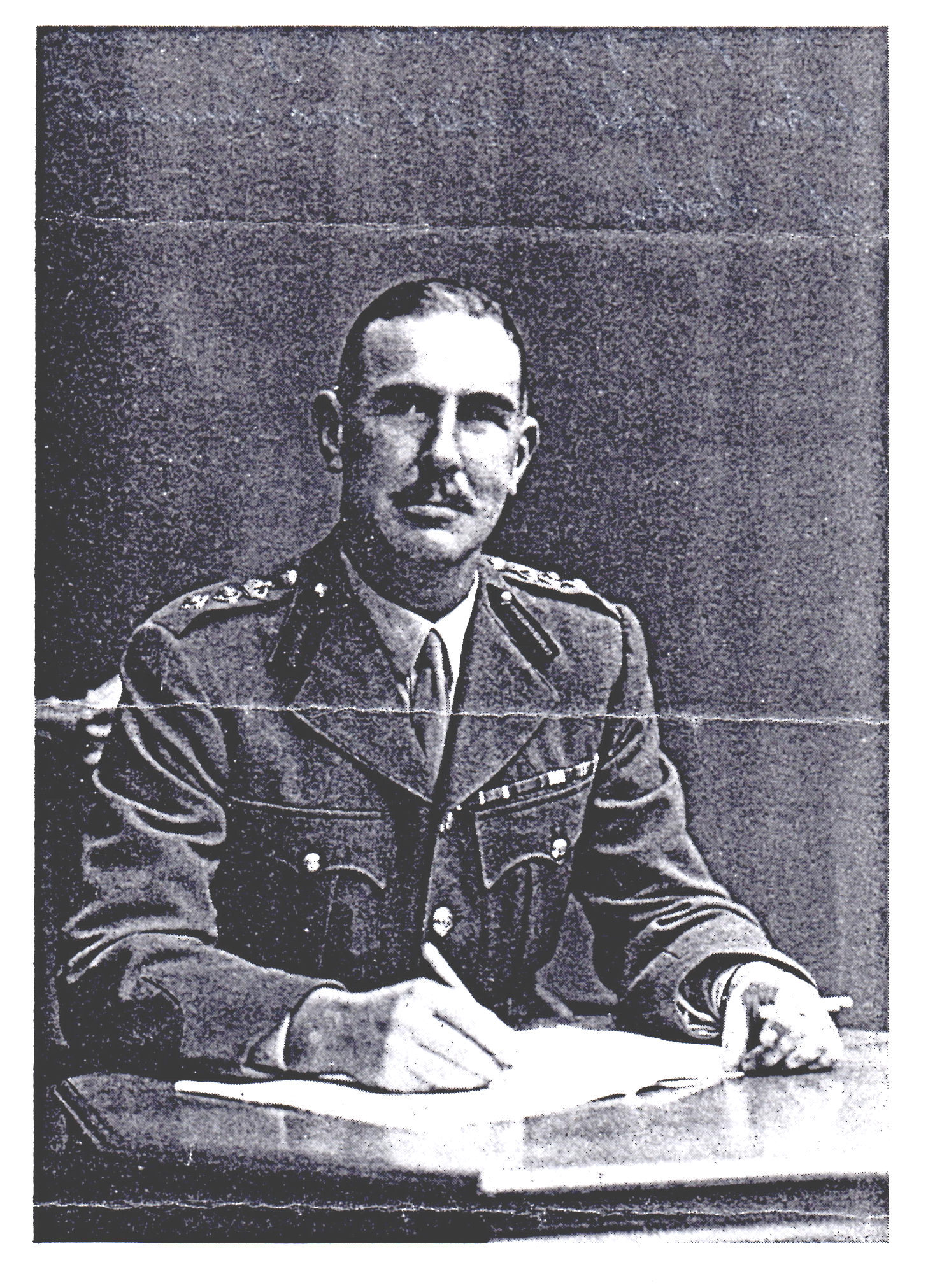

Figure 1. Major General L. D. Veitch, CB, CBE.

(Image courtesy of Wikipedia)

MAJOR GENERAL LIONEL DOUGLAS VEITCH, CB, CBE

Royal

Engineers

by

Lieutenant

Colonel Edward De Santis, MSCE, BSAE, PE, MinstRE

U.S. Army

Corps of Engineers (Retired)

2011.

(Revised 2025)

Figure

1. Major General L. D. Veitch, CB, CBE.

(Image

courtesy of Wikipedia)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Although a good deal of information of an official nature had been written about Major General Veitch, the official documents did not provide any insight into the nature of the man. To gain that insight it was necessary to seek out individuals who knew him and had either served with him or for him. My search for information began with Colonel M.B. (Bill) Adams, Hon. Secretary, King George V's Own Bengal Sappers & Miners Officers Association. How fortunate I was to have decided to start my inquiries with Bill Adams. Right from the start he took an active interest in the project and with great energy began searching for officers who knew Major General Veitch. Needless to say he was successful. In addition to the information which he himself was able to supply about the General's life, he was also successful in contacting Brigadier H.R. Greenwood, Colonel W.G.A. Lawrie, Lieutenant Colonel W.A. Shaw, Colonel E.H. Ievers, and Colonel D.C.S. David. Each of these gentlemen was extremely eager to assist me in my research efforts and it was the information contained in their letters which provided the greatest amount of detail concerning Major General Veitch's life and military career. Additionally, Bill and Frances Adams were kind enough to accommodate my wife and me in their home in September of 1988, thus giving me the opportunity to interview not only Bill, but also Colonel David and Colonel Ievers. These personal interviews added much to my knowledge of General Veitch.

I am also indebted to Major J.T. Hancock and Mrs. M. Magnuson of the Royal Engineers Corps Library for supplying me with the memoir from the RE Journal, written at the time of Major General Veitch's death. I am also grateful to them and to the Editor of The Sapper for publishing my letter requesting information about the General from anyone who knew him.

In response to my letter to The Sapper I was contacted by Colonel E.A. Ievers and the late Major E. Odell, both of whom had some very interesting bits of personal information to share about Major General Veitch. Unfortunately, Ernie Odell passed away on the 29th of August 1988, before this work could be completed.

Finally, I am grateful to my good friend Alan Rolfe for his persistence in obtaining copies of the General's birth and death certificates, and an extract copy of his will. All of these documents provided much useful information and helped to plug some gaps in the narrative.

Many other individuals wrote to me with information concerning Major General Veitch. Credit has been given in the text or in the references to all who contributed. Although I may not have specifically acknowledged the contribution of each, my sincere thanks go out to all who helped.

PREFACE

This started as a "man behind the medals" project when the full group of orders and medals awarded to Major General William Lionel Douglas Veitch were acquired in the United States by a friend of the author and fellow medal collector. Knowing that I could find my way round in my circle of Royal Engineers friends, I was asked to research General Veitch's life. As one reads the text of this work it will become obvious that the orders and medals of Major General Veitch consist of the following:

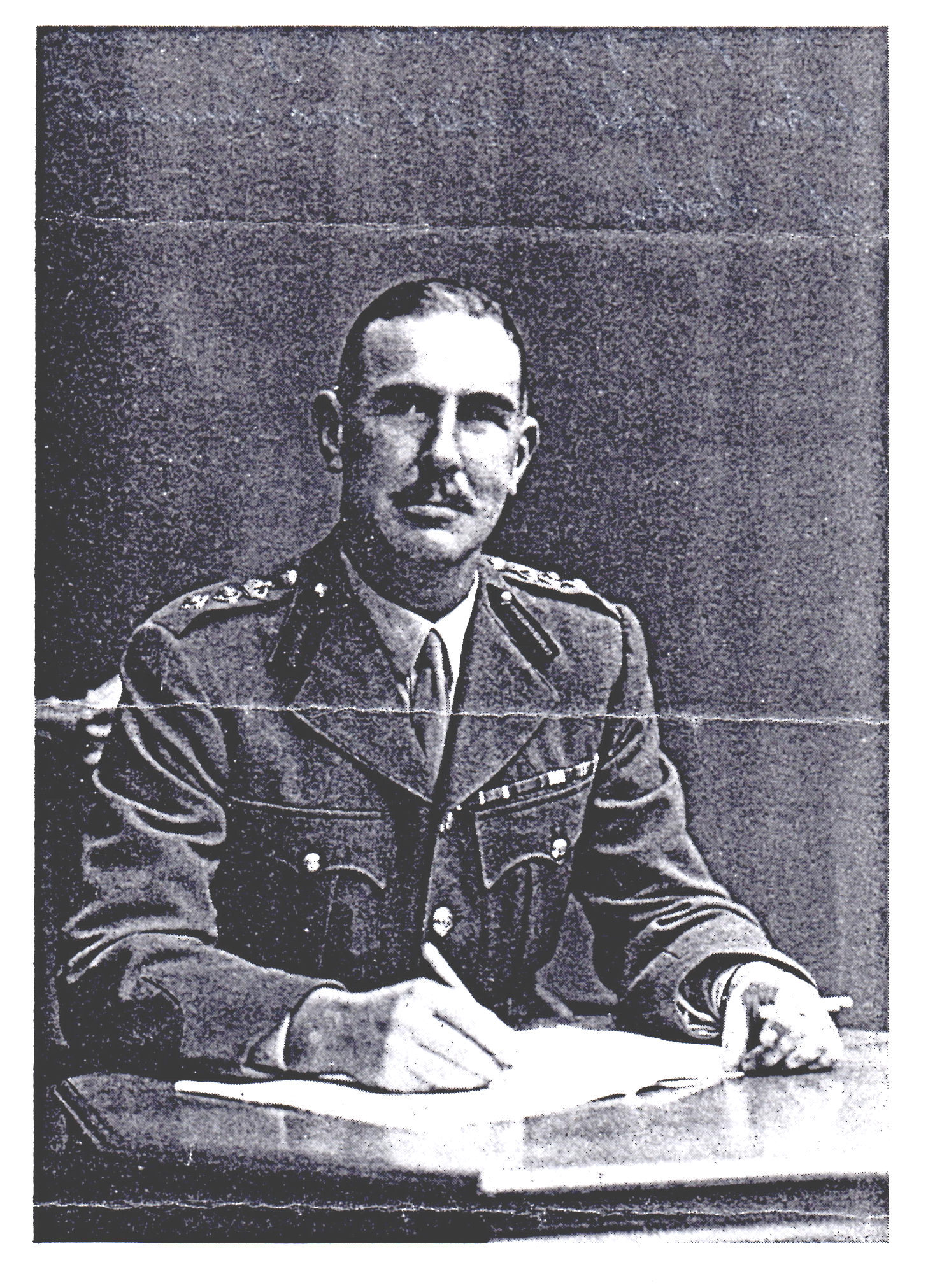

Figure

2. The Medals of Major General Veitch.

(Image courtesy

of Noonans Mayfair)

1. Order of the Bath (Military), third class (C.B.)

2. Order of the British Empire (Military), third class (C.B.E.), second type.

3. Order of the British Empire (Military), fourth class (O.B.E.)

4. India General Service Medal 1908-35 (GV) with one clasp, North West Frontier 1930-31, and Mention-in-Dispatches (MID) oak leaf.

5.

India General Service Medal 1936-39 (GVI) with one clasp, North West

Frontier 1936-37, British issue, and MID oak leaf.

6.

Defence Medal

7.

War

Medal

8. Coronation Medal 1953 (EII)

9.

Pakistan Independence Medal

When found in the United States all the medals were mounted "Court" style for display and were found to be in nearly extremely fine condition.

Although the research project was started by my friend's acquisition of the medals, it soon became apparent to me that the work had some greater importance. I found in reading the letters written to me by Major General Veitch's fellow officers that there was a desire on their part that his story be told," some for historical purposes and some because of the esteem in which he was held by individuals who had served for him. While it is always difficult to reconstruct a life by long distance from the best sources, I trust that my efforts will do some measure of justice to a man who was one of the prime movers in shaping the history of the Bengal Sappers and Miners and the Royal Pakistan Engineers. To those who read my story of the life of Major General Veitch and find what they believe to be errors or inconsistencies, I ask your indulgence. His life story has been reconstructed mainly from primary sources; that is, from the personal remembrances of many people who have had to search their memories over a period of some 50 odd years. There were inconsistencies and conflicting opinions with regard to what happened and when during Veitch's lifetime. I have had to weigh the evidence presented to me and I have had to compare the stories told to me with each other and with official records and documents. It was therefore my task to decide which story and which facts appeared to be most accurate. If I have decided incorrectly, I apologize and ask that those individuals whose facts or accounts I did not use forgive me if you feel slighted in any way. Hopefully, I have not misquoted any of my sources. If I have, I am certainly prepared to correct any defects noted.

I. THE EARLY YEARS

William Lionel Douglas Veitch was born on the 21st of November 1901 at Springfield, in the Parish of Dunbar, a small town on the North Sea at the base of the Lanmermuir Hills approximately 25 miles due east of Edinburgh. Dunbar was an old fishing port and royal burgh, and was prominent as a seaside and fishing resort.

William was the son of the Reverend William Veitch, M.A., T.D., the Minister of Belhaven, East Lothian, Scotland, and his wife Helen Flowerdew Veitch (nee Lowson). The Reverend and Mrs. Veitch had been married on the 23rd of October 1888 at Dundee and were residing at 12 Lennox Street, Edinburgh at the time of their son’s birth. William's birth was registered at Dunbar on the 10th of December 1901(1, 2). The Reverend and Mrs. Veitch also had a daughter, Vera Cecil.

Veitch entered Edinburgh Academy in 1909 and later gained admission to the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich from which he was commissioned a Second Lieutenant in the Royal Engineers on the 13th of July 1921 (3, 4). Upon commissioning he attended training at the School of Military Engineering at Chatham with No. 5 Young Officers (Tuck's) Batch. While at Chatham he was a whipper in to the RE Beagles.

II. EARLY SERVICE IN INDIA

On the 13th of July 1923 Veitch was promoted Lieutenant and on the 31st of January 1924 he joined the King George's Own Bengal Sappers and Miners at Roorkee, India (5). Shortly after his arrival in India, on the 12th of March 1924, he was appointed Officer Commanding, Calcutta Defence Light Section. This unit consisted of one Jemadar, seven British Non-Commissioned Officers, and 17 Indian Other Ranks and was organized to carry out searchlight duties with the auxiliary forces. It also provided some workshop facilities for the local garrison. During his command of this unit, Veitch was continually uncertain of the status of his command, as the unit constantly suffered from not knowing if and when it would be disbanded (6). Between 1923 and 1925, all the Defence Light Sections in India began to suffer in strength and were reduced gradually to mere cadres. As a result of these reductions Veitch remained with the Calcutta Defence Light Section for just under a year, and on the 5th of January 1925 he was posted back to Roorkee and assigned as a company officer with No. 7 Bridging Train under Captain H.F. Barker. Upon his return to Roorkee he gained valuable experience with many units in a number of different assignments within the Bengal Sappers and Miners. His tour with No. 7 Bridging Train ended on the 10th of June 1925 when he was posted to "A" Depot Company as Assistant Superintendent of Instruction. During this period the Superintendent of Instruction was Lieutenant Colonel L.V. Bond (later GOC Singapore). His duties during this posting involved Fieldwork Instruction for recruits and instruction in other Fieldwork Courses.

Bill Veitch's first opportunity at command of a field company came shortly thereafter on the 29th of September 1925 when he was appointed OC, 3 Field Company, Bengal Sappers and Miners at Roorkee on a temporary basis. He took over command of this company from Major B.H. Robertson, son of Field Marshal Robertson of Great War fame. During this period 3 Field Company prepared an artillery practice camp and airfield some four to five miles from Roorkee. After a little over a year in command of 3 Field Company he joined 5 Field Company on the 25th of October 1926 as a company officer.

Lieutenant Bill Veitch moved to Rawalpindi with 5 Field Company in October of 1927. Captain H.N. Obbard commanded this company until the l6th of October 1927 when Captain K.G. Maclean (later Lieutenant-General) assumed command. As a Colonel, Obbard was to command the Bengal Sappers from September of 1940 to the 12th of December 1943 when Veitch, then a Colonel, took over the command. Years later, as a Lieutenant-General, Sir Kenneth Maclean, with others, was responsible for drawing up the plans for operation OVERLORD and later became Chief Staff Officer at the Ministry of Defence. lan Jacob (later Lieutenant General Sir lan Jacob) who had also served with the Bengal Sappers and Miners assisted Maclean with the OVERLORD plans. Sir Kenneth retired in 1954 to Melrose in Scotland and remained a close friend of General Veitch after they had both retired. Sir Kenneth died on the 5th of June 1987.

On the 7th of January 1928 5 Field Company took part in Brigade training at Usman Khattar. It then moved to Sang Jani for Rawalpindi Divisional Maneuvers and marched to Akora, near Nowshera, for fieldworks training.

On the 7th of March 1928 Veitch returned to Rawalpindi by train where he was posted as Officer Commanding, 4l Divisional Headquarters Company. He remained in this assignment until the 31st of December 1929 when he was posted to the Military Engineer Services as Garrison Engineer of the Wana Road Project at Tanai in Waziristan. The Military Engineer Service to which Veitch was assigned evolved from the Public Works Departments in India, first as the "Military Works Department” and later as the "Military Works Services". The MES controlled all military engineering works in India and Burma except in a few small stations where these works were in charge of the Public Works Department. The MES controlled all the works of the Royal Air Force, and in addition they were in charge of all civil and military works, except railways and irrigation, in Baluchistan and the tribal areas of the North West Frontier Province (7).

The year 1930 shared with 1919 the distinction of being the most critical period on the North West Frontier since 1897. It opened quietly; yet, by the middle of the year, most of the Frontier was smoldering and some of it within an ace of bursting into flame. Common cause among many of the tribes had been secured by agitation and propaganda. Discontent had not reached serious proportions in Chitral, Dir, Swat and Hazara, but it became necessary for the British forces to bomb some Mohmand lashkars during May, and to attack some tribal gatherings in Bajaur during June and July. The rebel organization known as Redshirts, under Abdul Ghaffar Khan, had been causing trouble along the Mohmand Frontier and in the border villages, so that it became necessary to establish a blockade line and an improved system of roads. A few minor actions were fought, but most of the period was one of engineer effort, spent in making roads and building posts. The idea was to try to make the tribesmen trade, rather than raid. It was during this period that Veitch took part in operations on the North West Frontier for which he was awarded the India General Service Medal 1908-35 with the clasp North West Frontier 1930-31. He also received a Mention in Despatches for his good work during this same period, thus entitling him to an oak leaf for his India General Service Medal.

In 1932 Veitch returned to regimental duties with KGO Bengal Sappers and Miners as OC, 43 Divisional Headquarters Company. On the 1st of June of that year he was posted as Assistant Superintendent of Park. He was promoted Captain on the 13th of July 1932 and shortly after his promotion, on the 17th of September, he was appointed Superintendent of Park (Workshops), with Lieutenant J.H. Blundell as his Assistant (8). Blundell later became CRE of 4 Indian Division and was killed in action in March of 1943 in North Africa.

Veitch

relinquished his appointment as Superintendent of Park to Major

Wishart, R.E. on the 3rd of March 1933 and on the l6th of March he

rejoined 43 Divisional Headquarters Company at Roorkee.

While commanding this unit a section of his company under Lieutenant

E.H. Ievers were engaged in earthquake relief operations at Bihar

(17). Veitch remained at Roorkee until the 3rd of March 1935

when he moved with his company to Rawalpindi. On the 30th of

November 1935 he again returned to 5 Field Company, Bengal Sappers

and Miners at Roorkee, this time as the unit's commander.

During

the winter of 1936/37, Veitch went home to England on leave. He

returned to India in time to move his company to Bannu in Waziristan

on the 5th of March 1937. He again took part in

operations on the North West Frontier where his company joined

Wazirforce in operations against the Faqir of Ipi. The

operations undertaken in the summer of 1937took place in the area

enclosed roughly by the old Circular

(Bannu-Razmak-Tank-Bannu) Road. This road ran through rugged

country in which water could be obtained only from the Tochi,

Khaisora, Shak-tu and Tank Zam streams and from new springs.

Fortunately, the services of no less than six field companies and a

D.H.Q. company of Sappers and Miners were immediately available

for the operations. Among these units was Bill Veitch's 5

Field Company.

The Sapper units were called upon to perform varied tasks. The companies repaired bridges and culverts, built blockhouses, supplied camps with water, and even erected ice-factories to provide ice for armoured cars and tanks. Operating with columns on the march the companies demolished towers, made tracks, and built piquet posts covered with wire screens as a protection against bombs (i). All this in addition to never-ending road making, the supervision of working parties, and assisting in the construction of two large defensible posts for garrisons of the Waziristan Scouts.

Specifically, Bill Veitch's 5 Field Company was responsible for water supply and local road construction at Dosalli. After a short period there the Company moved to Coronation Camp, where the next five months were spent on road construction from Dosalli to Ghariom and on to Shawali, and on providing semi-permanent water supply to various posts and road construction work at Bhittani Camp. In all this work Veitch’s previous experience with the Military Engineering Service stood him in good stead. For his participation in these operations he was awarded the India General Service Medal 1936-39 with clasp North West Frontier 1936-37.

Lieutenant Colonel W.A. Shaw who first met Veitch in Waziristan in 1937 remembers him as "a cheerful but fiery and independent character" (9). Having only just joined his own company, No. 2, and having only a very sketchy knowledge of Indian troops and their language, Shaw found Veitch's knowledge of the country and of the men under his command to be very impressive. Shaw recalls that Veitch had his private car with him during the 1937 operations. It was a large estate model which held about six people and was known to all as "the goldfish bowl". It was not really a cross-country vehicle, but was used by Veitch largely as such and behaved remarkably well for its poor ground clearance.

In December of 1937 Veitch returned to Roorkee where he took up residence in No. 2 Bungalow, a thatched roof structure near the Mess. No. 2 was the best of the bachelor bungalows and Veitch shared it with Lieutenant J.R. (Dick) Connor.

In February of 1938 he was appointed OIC Workshops (known as C.I.W.) of the Bengal Sappers and Miners. As C.I.W. he was responsible for the basic trades training of recruits and more advanced upgrading courses for Indian Other Ranks covering all the trades and grades required by the S & M units. The Sappers were keen to get qualified in trades because doing so affected their pay. It was typical of Veitch's concern for his men that it irked him that many men qualified as Artificers could not be paid as such because of an "Artificer Ceiling" which had been imposed by the Indian Finance Department.

In the Workshops Veitch had one British officer (Dick Connor) as A.I.W. and a number of British warrant officers and NCOs as trade instructors. As Colonel D.C.S. David recalls (10):

"To newly arrived junior officers, what went on behind the gates of Workshops was largely wrapped in mystery and only gradually did one come to realize how important it was for the field units, and for the Corps as a whole, that a high standard of proficiency in all the trades on our establishment should be reached and maintained. This Veitch certainly achieved. In everything, he set and expected the highest standards".

During his tenure as C.I.W. Bill Veitch increased the capacity of the Workshops by sixteen fold so that by the end of 1940 there were as many instructors as there had been students the year before. This enormous and rapid expansion was undertaken very smoothly, with no fuss or sense of pressure, thanks to Veitch’s superb organizational abilities. In addition to expanding the Workshops during this period, Veitch took a personal hand in upgrading the Workshops Printing Section from platten to flat-bed presses (28).

Veitch's handling of disciplinary matters in the Workshops is well illustrated by the following story told by Major Ernie Odell (11) who had served under him as a Non-Commissioned Officer;

"In the fitters shop (at Roorkee) we had a trainee who was ill fitted to become a fitter. He was to cut a square hole 1" by 1" in a piece of 1/4 inch plate, then cut a piece of the same metal to fit the hole. He tried several times but made a mess of each. The Naik under whose training he was working and the British Sergeant Major of the fitters shop brought the man before me, asking if he could be given another trade. I said give him one more chance and bring the results to me and we would send him and the evidence to get his trade changed. This was in the afternoon. The Naik was due for night guard duty and therefore excused one hour from workshops at the end of the afternoon, and in the morning was excused coming to workshops until after breakfast. When he arrived the trainee handed him a perfect job. The Naik asked him where he got it from, only to hear that he himself had made it. Of course the Sergeant Major brought the Naik and the trainee in front of me. He said he had done the job. The Naik said he could not have done such a job himself in that time. A Captain Graham was O.C. Workshops at that time, so I took them along to him and said I had a man to be sent to the Training Battalion on a charge. The O.C. said he did not think we should do so, but give him another chance. I pointed out I was not so much concerned as to his abilities, but very much so in his lies to us, and even more so, who did the job, for I was sure it was ready made outside of Workshops, and there must have been a sale for such a thing, although we had such a good set of Indian instructors who would be around looking at every man in progress. Anyway, I pointed out that I would write out an official version of the affair. So the Captain told me to get on with the case. I walked out of his office a bit disgusted when I met Captain Veitch. He said, 'Hello Odell, you are not looking your usual self, what's wrong'? I showed him the beautifully made trade test. He wanted to know who made it. I told him I would very much like to know as the man that claims he made it is a liar. I then told him what had happened. He asked me which unit he came from. I told him it was D.H.Q. Company. He immediately said he was glad to hear that as he had just taken charge of the unit whilst the O.C. was on long leave.

So next morning they all paraded in Captain Veitch's unit office. The Naik told his story, then the British Sergeant Major. The trainee was asked if he had done that work himself. He said he had done so. Captain Veitch told him that he was a liar and as it was a serious offence sentenced him to 14 days R.I. (Rigorous Imprisonment), which meant digging a 6 ft by 5 ft by 3 ft trench every day during the period of the punishment. He then asked the prisoner what he thought of that. The reply was that he still maintained he had done the job. Veitch then said that he himself was a fair man and he would give the order to take the man back to Workshops and give him the steel to do another one in the same time as the produced one. If he could not do the job he would receive 28 days R.I. The man decided to accept the l4 days originally imposed as punishment."

On the 18th of February 1938 Veitch received his second Mention in Despatches for his good service on the North West Frontier and an oak leaf for his second IGS Medal. On the 1st of August 1938 he was promoted Major and on the l6th of August of the same year the London Gazette published his award of the Order of the British Empire (Military), Fourth Class (O.B.E.).

During the remainder of 1938 and 1939 life took on a more casual flavour for Veitch. According to Colonel David, one saw most of Veitch in the Mess. Like many Bengal Sapper officers he was a dyed-in-the-wool bachelor whose social life was centered on the Mess. In fact, he was considered by some to have an anti-woman bias. However, in truth he was probably a proponent of the old rule in the Bengal Sappers and Miners which used to be that "Subalterns must not, Captains should not, Majors may and Colonels should get married". Despite his possible adherence to this old philosophy, Veitch always showed the greatest kindness to married officers and their wives and helped them whenever he could.

One might be tempted to view Veitch's attitude towards women in the way that John Masters describes the life of British officers in India during this same period (12). Masters describes the situation in the following paragraph;

"It is useless to pretend that our life was a normal one. Ours was a one-sexed society, with the women hanging on the edges. Married or unmarried, their status was really that of camp followers. But it is normal for men to live in the company of women, for if they do, they do not become rough or boorish, and the sex instinct does not torment them. In India there was always an unnatural tension, and every man who pursued the physical aim of sexual relief was in danger of developing a cynical hardness and lack of sympathy which he had no business to learn until many more years had maltreated him. Of those who tried sublimation, some chased polo balls and some chased partridge, some buried themselves in their work, and all became unmitigated nuisances through the narrowness of their conversation. And some took up the most unlikely hobbies, and some went to diseased harlots-some married in haste..."

Indeed, Veitch seems to have lived in a one-sexed society as described by Masters; however, whatever relief he may have needed from any "unnatural tension" it appears he got from work, fishing, shooting, and polo. In fact, one is inclined to feel that Veitch may have had a fear of becoming "trapped", so to speak, by a husband-seeking woman and that his alleged anti-woman bias was nothing more for him than a means of self-protection. Perhaps he felt that he could not dedicate himself to his work and to a wife with equal energy, or at least with the energy that each deserved. Philip Mason (30) in his book "The Men Who Ruled India" provides a commentary on men he calls the Titans of the Punjab. His outlook on this situation is quite different from that of Masters:

"Few of these men married; they spoke constantly of their mothers in terms as emotional as they use of their religion. Passion blazed in them and was harnessed to work and to bodily rigour. Marriage before middle age was an infidelity."

"No doubt they were hard men to live with, sometimes to torture themselves and those near to them. But they were dynamic; there is a size and force to them. Without their taut strung emotions they would not have achieved what they did."

Much of what Mason says can be seen in Veitch. Officers who knew Veitch well say that his passions were those described by Mason rather than by Masters. Indeed, Masters' social experiences as an officer in India serving with infantry troops are described by Engineer Officers as being quite different from theirs.

In October of 1938 Veitch played on the Bengal Sappers and Miners Polo Team in the Dehra Dun tournament. He was an excellent horseman and a strong polo player. Lieutenant Colonel Shaw had few contacts with Veitch professionally at this time, but they did meet on the polo field where Shaw says that Veitch was both competent and aggressive; both traits true to character.

Veitch was a proficient shikari with both rifle and scatter gun. In December of 1939 he went tiger hunting in the Dechauri jungle with Dick Connor over Christmas and Connor shot an 8 foot-1 inch tigress. Tiger shooting during the Christmas season apparently was somewhat of a tradition with Veitch. In December of 1940 he was again in the jungle, this time accompanied by a junior officer named Bernard Feilder (later Sir Bernard M. Feilder, CBE). Because of Veitch's close rapport with his Punjabi Mussalman, he usually chose one or two to go along with him as orderlies on these shooting trips.

In 1940 Veitch was appointed to command of the Training Battalion, KGVs Own Bengal Sappers and Miners at Roorkee. An officer who served under him in the battalion found his method of command to be clear and decisive. He was considered to be a man of great judgment and a CO one could totally trust. He knew exactly where he was going and what results he expected; however, he always let his subordinates get on with the job with the minimum of interference (29).

In 1941 he became Commander Royal Engineers (CRE) for the 19th Indian Division in Southern India. He remained in this assignment until the New Year when in January 1942 he was posted as a Staff Officer, Indian Army Headquarters, at Delhi. Later in the same year he was appointed Commandant of No. 1 Engineer Group, Corps of Indian Engineers at Lahore. The designation "Corps of Royal Indian Engineers" was not conferred until the 1st of February 1946. During this same period the Bengal Sappers and Miners were also re-designated the Bengal Sappers and Miners Group and subsequently the Bengal Engineer Group (13).

As Commandant of No.1 Engineer Group he was responsible for raising certain specialist engineer units for employment as Corps, Army and General Headquarters Troops, in particular Artisan Works Companies, Electrical and Mechanical Companies and Machinery Equipment Companies. This was an important task for which his marked organizing ability eminently suited him. Brigadier H.R. Greenwood (l4), who at the time was 2nd In Command of No. 1 Engineer Group, recalls Bill Veitch as a very able man and a hard worker, and somewhat of a loner, although he did have one very close friend, Colonel Dick Connor, with whom he maintained a very close life-long companionship. Brigadier Greenwood also recalls that Veitch did almost everything through his Indian Officers (VCO's), whom he immediately got to know. He also took an interest in training British officers with no knowledge of the local language of their troops, as he himself was completely fluent in Urdu (17).

Veitch was very meticulous with his work habits and had little patience with anyone who would draft rules and regulations which could not in practice be enforced. An officer who knew him well claims that "he never allowed papers to pile up in his pending tray. His chief clerk was trained to put all the regulations and cross-references into a bundle tied with tape" (l4). He was quick to deal with a problem, make a decision, and throw the bundle in his "out" tray. Good time management and decisiveness were among his strong points. As far as his command of No. 1 Engineer Group is concerned, Veitch made a successful Group out of a complete shambles.

Graeme Black (21) recalls that in straightening out No. 1 Engineer Group at Lahore Veitch brought into the unit with him a good number of selected Bengal Sapper and Miner personnel. When some years later Black was commanding an Artisan Works Company in Rangoon, whose Depot had been No. 1 Group at Lahore, he discussed with some of his men the poor standards which had existed in that Depot. The men confided to him that “life was very easy till Veitch Sahib arrived with those kale half tope wallahs"(ii). Apparently Veitch’s hard driving style of command was well remembered by the men who served under him.

Another officer who knew Veitch well over a number of years in India admired him enormously and took him as a role model of how to command Indian troops. Veitch copied the old heroes in many ways (iii), possibly unconsciously, but this method of leadership and command did not always find approval among other British officers. He was known to sort out the VCO's he could trust implicitly and relied on them directly over the heads of British officers who did not know the language and customs of the men as well as he did. He used to get men to come to his bungalow and sit on the porch and gossip; such was the manner of his association with his Indian officers.

Graeme Black (21) indicates that the curious system in the Indian Army of consulting Indian NCOs and VCOs over the heads of their officers was almost a general practice, and probably a peace time habit. The young British officers arriving in India were sent to their units for the most part with little or no knowledge of the country, the people, the procedures of the Indian Army, and worst of all little knowledge of the language. It was extremely difficult for many of them to function as an effective channel for transmitting orders to their men. Similarly, they had difficulties in supervising the execution of the orders and in passing information back up the chain of command. They could not effectively judge the morale of their men, detect grievances at an early stage and effectively nip in the bud any developing trouble. The "back stairs" chain of command and intelligence, though it greatly incensed young officers, appears to have been necessary for the proper functioning of the military organization of the time. Black presents his own analysis of the situation when he writes:

"When I look back at my own ignorance and ineffectiveness as a young officer and the responsibilities thrust upon my units I realize all too well how much was owed to the long service and experience of my VCOs and NCOs who uncomplainingly supported me. I am also appalled at the assumptions of superiority which were made by young war conscripts like myself just because we were British and officers, and I am amazed at the cheerful acceptance of us by our troops. And yet it worked. Great work was done. Great affection flowed both ways."

III. COMMANDANT OF THE BENGAL SAPPERS AND MINERS

On the 12th of December 1943 Veitch returned to regimental duties once again, this time as Commandant of King George's Own Bengal Sappers and Miners and Station Commander at Roorkee. Shortly thereafter, on the 12th of February 1944, he received a temporary promotion to Colonel, a rank commensurate with his new command (15). On the 8th of June 1944 he was also awarded the Order of the British Empire (Military), Third Class (C.B.E.). From the 20th of October to the 18th of November 1944 Colonel Veitch visited Bengal Sapper and Miner units serving in Italy (17). During his travels in Italy he visited 5 Field Company which was temporarily under the command of Bernard Feilden, the young officer with whom Veitch had gone tiger shooting in December of 1940. Despite their being in the line, and despite the foul weather, the Company put on a really smart parade for their old Commander (27).

By the close of the war in 1945 Veitch was also entitled to the Defence and War Medals for his service during the conflict. That he was not entitled to the Italy Star by virtue of his 1944 visit is probably due to his "non-operational" status while with the units he inspected despite the fact that his inspection tours took him very close to, if not into, the front line (18).

During his tenure as Commandant he was tremendously energetic, decisive, and encouraging to those who served under him. Some of his subordinates felt that he should have delegated more authority, as he dealt directly with some dozens of individuals, and there always seemed to be a queue waiting to see him. One of his idiosyncrasies seems to have been the habit of instantly answering the telephone when it rang, regardless of who was with him at the time. If the phone rang, he would break off his conversation to answer it. If you were low in the queue, it paid to go to the phone and ring him for a quick answer. Despite his efficiency and good management practices with regard to his personal time, he seems to have been inconsiderate of his subordinate's time. His unwillingness to delegate authority to his subordinates must surely have put a greater burden on him than was necessary and would have made him what we know of today as a "workaholic".

In fact, Veitch was described by some fellow officers as a “glutton” for work and seemed not to need more than three or four hours sleep a night. He was able to control the multifarious details of the Bengal Sappers Centre and the Group (as the Corps had been renamed at this time) in a way that few other people could have done, and still maintain standards of efficiency not far below those of pre-war days. He tried to fill key positions with men who had seen active service in one or other theatre of war and who therefore knew the conditions for which new units and reinforcements sent to units in the field must be prepared. However, with the large expansion that had taken place men returning to the Centre from overseas were often upset to find that some who had remained in India and seen no active service had been promoted above their seniors overseas.

Aside from the serious aspect of Veitch's nature during his stint as Commandant, Graeme Black (23) treats us to some wonderful anecdotes with regard to his more mischievous side;

"Bill was perfectly aware of the reputation he had for irascibility and made use of it from time to time. When, for instance, he was too busy to go round the Cantonment (of which he was Station Commander - a quite separate appointment from being Commandant of the Bengal S & M who were the majority occupants of the Station but not the total) he would put his golden retriever on the back seat of his station wagon and tell his driver where to take a round tour. I have seen work parties redouble their efforts and VCOs and even officers rigidly saluting the passing car which had its flag up - illegally."

"He had little time for higher authority himself if he thought it was wasting his time. I remember a visit by one of GHQ Delhi's staff. Veitcho (iv) tossed the appropriate file to one of his Grade II officers and told him to take the staff officer round to see whatever it was he came for. The tour became frosty in spite of efforts of our chap to cheer it up. Bill did not appear at all. When the S.O. left for Delhi our man looked at the file he had been carrying under his arm - labeled "Visits; Unimportant".

"On another occasion, summoned to Area HQ to attend a conference in spite of his protests that the State of Emergency due to impending Partition left him no time for this, he sat at the back of the room working on files he had brought with him, and when rebuked by the Area Commander, blandly stated that he had not wanted to come in the first place, was not in the slightest interested in the subject under discussion and intended to get on with something useful. He got away with it!"

"He could be devious when it was needed. In the Indian Army a commander had two sources of information about the men under his command. The official route through ascending ranks to him, and the unofficial via the VCOs. On one passing out parade of recruits in the Training Battalion in my Company an excellent platoon showing off their paces very well met with no approval at all and Veitcho was getting visibly furious. To our astonishment they were not passed and ordered a further week’s training. As he left the ground Veitcho suddenly rounded on a VCO and said 'who the ... is that fellow with his medals squint?', and stormed off on being given his name. In that evening's orders the hapless Subedar who was in fact very distinguished and due to retire that year found himself posted to Burma. Months later I found that he had been having pretty young recruits into his room for reasons which were quite unmilitary and that the whole day's debacle of a pass-off failure had been cooked up to get the man out of the way without resorting to a full court martial which could have deprived him of his pension which he had fully earned and which might not have convicted him since information at that stage was simply what had come up by the back door."

These wonderful stories do much to put human dimension to a man who to some might have appeared to be a stern, unyielding commander and disciplinarian.

Anecdotes aside, the difficult tasks of command still had to be dealt with effectively. The sudden end of the war with Japan in August of 1945 threw everything into turmoil as headquarters at all levels tackled the problems of demobilization and resettlement, and planning the shape of the peacetime Army and its future training, all against a background of political developments which were to lead to partition and the birth of the independent states of India and Pakistan. The year 1946 brought to Colonel Veitch the responsibilities for reorganization of the Bengal Sappers and Miners along class lines, which was a very controversial matter. Early in 1946 the Commander-in-Chief laid down that no unit of company size or smaller was to contain more than one class. This meant that all Bengal and Bombay Sapper and Miner companies, which for generations had had one section of Mussalmans, one of Sikhs and one of Hindus, had to exchange sections so that each would become one-class. It fell to Veitch to carry out this wholesale reorganization of the Bengal S & M units. At the time the change was most unpopular, being seen as involving the gratuitous destruction of the camaraderie between men of different religions that had grown up during the war, in which the Army was giving a much needed lead to the country. The C-in-C was, as usual, farsighted. Whether the reason for the change was fear that the Indian officers who would soon replace British as company commanders might be suspected of favouritism towards their own class, or anticipation of the possibility of the Army being divided in step with the division of the country in the event when partition took place, the fact that companies had already been reorganized on a one-class basis made the division of the Corps between the new India and Pakistan less traumatic and difficult than it otherwise would have been.

IV. THE MOVE TO PAKISTAN

Veitch relinquished command of the Bengal Sappers and Miners in 1946 and on the 18th of January 1947 he received promotion to the substantive rank of Lieutenant Colonel.

On the 1st of November 1947 Lieutenant Colonel Veitch was promoted temporary Brigadier while serving as Deputy Chief Engineer, Northern Army, India, which appointment he was holding on the Declaration of Independence in 1947. After Independence he was named Director of Works and shortly thereafter Deputy Engineer-in-Chief of the Pakistan Army and was installed at General Headquarters in Rawalpindi.

His good friend Dick Connor was at Sialkot, some 150 miles southeast of Rawalpindi, as Commandant of the new Pakistan Engineers Centre. The tasks they faced together were immense. A nucleus of staff including seven British Officers had arrived from Roorkee and had taken over what remained of the old Engineer Depot which had been formed in Rawalpindi early in the war to raise semi-skilled engineer battalions. The Engineer Depot was disbanded early in 1947 (24). Scarcely had they settled in before train load after train-load of Sappers - sometimes in formed units, but more often as mixed bodies sporting a variety of different badges began to arrive, often without warning. Each group had to be sorted out, accommodated, and a decision taken on each man as to whether he was to continue to serve or be discharged. There also arrived train after train of engineer equipment, to be unloaded without delay whatever time of day or night, sorted and stored.

In the task of building a new Corps Veitch and Connor, as in the past at Roorkee, worked hand in glove and with full understanding of one another's ways. Veitch looked after the GHQ end and Connor reduced to order the confusion at Sialkot where Veitch was a frequent visitor. Work at Sialkot involved the formation of a School of Military Engineering to organize and conduct the engineer training of Royal Pakistan Engineer officers. More urgently, much had to be done on all aspects of the training of Other Ranks, including the planning of recruit training, establishment of the trade training workshops and fieldworks training areas, preparation of course programmes, Boys Battalion training and sports. Local defence schemes and exercises also required high priority in the uncertain political situation, with the Indian Army deployed in Jammu only a few miles up the road. The Royal Pakistan Engineers News-Letter of 1 June 1948 provides a rather detailed account of these activities after Partitioning.

Some detail concerning the Boys Battalion would be appropriate here. The Commander-In-Chief, Field Marshal Auchinleck, had taken a keen personal interest in Boys training, and he had himself written the basic directive on which it was to be based. In 1945 there was a great shortage of leaders to provide the officers of the Army of the future. On the one hand was a somewhat effete aristocracy, on the other a swollen body of babus, prizing education as a passport to employment, but often lacking in moral fibre? It was hoped that through training in Boys Battalions, directed towards character building rather than technical apprenticeship, the peasant stock could be given the cultural and spiritual background, and the education, to enable it to fill the gap. Boys’ training was to be directed towards reducing the man, and the incipient technician. There was to be no specialized trades training; nothing more than general work at several allied trades, with most of the time spent on education. During the war Boys Battalions had been an invaluable source of tradesmen, most of them achieving artificer standard, and some of the S & M Commandants, including Veitch, were reluctant to give this up. Veitch had made his views on Boys training known in 1946, before Independence, when post-war training in India was being planned. It is not surprising that he and the other Commandants had a shorter view of the future than the C-in-C, who was acutely aware of the need to find leaders for the soon-to-be-independent India and Pakistan.

Such were the problems and preoccupations of Veitch during this period, and so slender were the resources. But through it all Veitch and Connor held things together and gradually saw the new Corps take shape and acquire strength and stability.

During the year 1947 Veitch was awarded the Pakistan Independence Medal. He continued in the position of Deputy Chief Engineer until 1950 when he was appointed to the position of Engineer-in-Chief of the Pakistan Army with the rank of Major-General. His promotions to the substantive ranks of Colonel and Brigadier came to him on the 15th of June 1950 and the 4th of August 1950, respectively.

On the 5th of June 1952 General Veitch was awarded the Order of the Bath (Military), Third Class (C.B.) while serving as the Colonel Commandant of the Royal Pakistan Engineers. His award was announced in the Birthday Honours List of 1952. He was also awarded the Coronation Medal (EIIR).

Those who knew him well understood that General Veitch considered his subsequent service with the Pakistan Engineers from 1947 to 1952 as merely a continuation of his service with the Bengal Engineers of pre-Independence days. The reason for his attitude of course was the fact that the Muslim element of the Bengal Sappers and Miners became a large and significant part of the Corps of Pakistan Engineers.

Officers who served with him and for him knew Bill Veitch as an officer of strong character and sturdy independence, who won a reputation as a very fine administrator, an excellent trainer and an indefatigable worker. He had a strong sense of justice and a hatred of what he considered unfairness; he had a high sense of duty and set very high standards, detesting slackness and inefficiency.

General Veitch would fight bitterly for those who he felt needed his help and protection and, as one close associate has put it, he could be difficult to deal with if he thought you were not one of the "family". During the partitioning of India and Pakistan his sentiments toward Pakistan were apparently not appreciated by his counterparts in India. The following extract from the "History of the Corps of Engineers, Indian Army, 1947-1972" perhaps indicates some of the feelings against him;

"When Independence came the Bengal Sappers had perhaps the least cause to rejoice. Partition agreements had required that one-third of the assets of the Corps should be transferred to Pakistan; and by reason of contiguity as well as resources, the decision was that a good part of the movable property at Roorkee would go across the border. With the disbandment of the Lahore and Sialkot wartime groups, the strength at Roorkee was about 6,000, a majority of whom had applied to go to Pakistan, among whom were most of the expatriate officers."

"The very tense and even suspicious conditions that had been created before Pakistan had made the carrying out of even the most routine regimental tasks a trying matter. All chance of a satisfactory and equitable execution of the division of assets was further vitiated by the blatant partisanship of the senior British officers, led by Colonel W. L. D. Veitch, the Commandant, who had opted for Pakistan and had been nominated its E-in-C."

"The resulting effects left Roorkee Centre reeling under the blows of successive depredations carried out by the departing British and Muslim Officers and men, who because of the disbandments of Lahore and Sialkot Groups, had formed the majority of the 6,000 Bengal Sappers at the time. Valuable movable property and Regimental trophies were carried away; entire records were filched ..."

Despite the tirade contained in the quotation above, his supporters are firm in their belief that he acted in the correct way during these troubled times. Some admit that the feelings in the Indian Engineers were perhaps understandable to some extent, but such severe criticisms were unfair. He was inclined of course to the Punjabi Muslims, as many British officers were, but he was never known to be unfair to the Sikhs or the Hindus.

Colonel W.G.A. Lawrie (16) provides a very clear account of some of the happenings in 1947 which may have caused the feelings described above among the Indian Engineers. Lawrie explains how in September of 1947 when he arrived at Roorkee after returning from the Boundary Force at Amritsar he found Colonel Dick Connor initially as Commandant there. Connor went off to be Commandant in Pakistan, but owing to some bad flooding conditions, the main rail line was washed away and the Muslim troops had to stay in Roorkee for three weeks or more. The trains had been loaded and were standing in the station during this period. Colonel Rex Holloway was to be Commandant at Roorkee after Dick Connor, but he was away on leave in Canada and Lawrie became Acting Commandant for some time, as he was the senior officer in Roorkee who had opted for India (v).

Lawrie conducted an inventory of the Mess at Roorkee and realized that quite a bit had been packed up for shipment to Pakistan. He protested and had a number of things unpacked and returned, including some whiskey and silver. The Mess silver that did ultimately arrive in Risalpur was definitely Pakistan oriented and, according to Lawrie, in their proper location.

Colonel Lawrie also recalls that at the time six large pieces of machinery (lathes, drilling machines, planers, etc.) which were in Roorkee in 1944/45 had also been moved to Risalpur. They had been useless in Roorkee at that time because spare parts were not available. In 1987, during a visit there, he saw the same machines in Risalpur, and they are still useless owing to non-availability of spares. In 1947 a large letter 'P' was painted on this machinery in Roorkee to earmark it for shipment to Pakistan and an 'H' was painted on whatever was to be left in Hindustan. Lawrie reports that in 1987, after 40 years, the ‘P’ markings were still on the unworkable machinery.

In 1947 Colonel Lawrie felt that Pakistan was getting a raw deal in the division of military assets. For example, most of the Ordnance Depots were in India and were immovable. He admits to understanding how officers like Veitch and Connor tried their best to rectify the situation at the time.

V. VEITCH AS A COMMANDER

Devoted to his troops, Veitch took endless trouble over their training and welfare. He even earned among them the name of "Vakil Sahib". The origin of the term "Vakil Sahib" had its roots in Veitch's appearance in court as "Prisoner's Friend" to defend a man of his unit. Veitch was most successful in making the prosecuting "Vakil" appear so foolish and confused in court that the poor man was forced to withdraw and the prisoner got off. As a result of this case any jawan who found himself charged in court with any offense promptly requested that Veitch appear to defend him. An order soon had to be issued that Veitch was not available to act as “Prisoner's Friend" for anyone other than men of his own unit.

In addition to his assistance with legal matters, his men could always go to him for advice and help over their domestic and village problems. He was especially in sympathy with the Punjabi Mussalman, and in particular with those from the Hazara District among whom he had many friends.

Lieutenant Colonel W.A. Shaw's chief memories of Veitch are of his intense interest in the welfare of his troops, in their home life as well as their military service. Shaw indicates that he had a special interest in the Hazara District where it was rumoured that he had property and that he planned someday to retire to this area. It was also rumoured that he intended to become a Mussalman. The latter rumour turned out to be unfounded and probably merely reflected the deep interest he took in the country and its people. Graeme Black (21) indicates, however, that Veitch did have land near Haripur in Hazara and that he used to stay there frequently as a refuge.

His interest in the welfare of his men even extended back to Scotland. According to Eyre Ievers (17), Veitch's mother provided hospitality to some of his VCOs when they visited Scotland.

He was never a keen games player, partially due to a knee injury in his schooldays, but he had many outdoor interests. A framed cartoon in his St. Boswells house, done when he was a junior officer, hints that he may have been a powerful swimmer in his earlier years. He played station polo regularly, but his main hobbies were fishing and big game shooting. His fellow officers remember well the shoots he organized in the forest blocks near Roorkee. He also had an interest in gardening, and used his Orderly Sapper Ahmed Khan to take charge of vegetable growing in his garden beside his bungalow. His interests were limited to these and nothing else outside of his work except freemasonry. Some of his fellow officers were somewhat resentful of his activities as a mason, in that he seemed to seek out the advice of masons among the British NCO's in preference to non-masons. Some of his fellow officers felt that this was bad for discipline.

The late Ernie Odell (11,22) was a Sergeant Major Instructor who served under Veitch at Roorkee when he was O.C. Workshops. Veitch and Odell had about 40 British Warrant Officers and NCOs working under them as instructors, together with a host of Indian instructors, hoping to teach trades to Indian recruits. Odell worked very closely with Veitch and was allowed a free hand with regard to the working of the shops, while Veitch attended to the paper work without interfering with the normal daily routine of his senior NCOs. However, Veitch always made a point of going round the shops daily, with or without Odell's assistance. Odell fondly recalled the respect with which Veitch treated his senior NCOs and claimed that they had "much fun" at times during Veitch's tours of the shops. Ernie Odell was the only individual who used the term "fun" with regard to any shared experiences with Veitch, perhaps indicating the existence of a playful, or certainly less serious, side of the man's character which was not readily apparent to all.

Odell was also a mason and describes below some of his contacts with Veitch as Lodge Brethren:

"Before he came to Workshops I saw a lot of him as he was a Freemason in the local Lodge. He was just senior to me as an office bearer, and for several years I followed him up the stairs of office until he reached the stage when he would take over as Master of the Lodge. Unfortunately he was posted away from Roorkee, which let me in one year before I had expected. At one of the ceremonies he was in charge and I was next. A part of the ceremony consisted of him speaking to me. I must mention that there were three steps running right across the front on which officers of the order usually sat. On this occasion there were none just where we were".

"During his talking to me at the bottom and close to the steps, I was facing him and saw a cobra coming along the bottom step from behind Veitch. As we were only going to be there for a few moments I was not unduly alarmed but kept my eyes on the snake. This annoyed Veitch, for of course he thought I was inattentive to what he was saying. Seeing me looking at something behind him, he turned around, saw the reason, and said, "Brethren the Lodge is at Rest" and with his wand of office, stepped to the cobra and killed the snake with a couple of blows which broke the top of his wand. Then turning round said "Brethren resume working", just as though nothing had happened, and the evening proceeded as usual." Clearly, Veitch was cool under pressure.

Although Veitch was a very private person, he was considered a loyal friend, a generous host, and an inspiration to the young by those who knew him best, although some of the younger officers admit to not being able to relax when around him. In fact, some junior officers held Bill Veitch too much in awe to try to break through the senior-subordinate barrier surrounding him and found socializing with him virtually impossible. However, these perceptions of the junior officers may have had more to do with the existing military social system of the time and less to do with Veitch's personality than these officers realized. The Indian Army of this period was a highly structured institution in which there was little vertical fluidity.

Despite these feelings of some junior officers, Bill Veitch was concerned for the welfare of his subordinates. Eyre levers (17) says that shortly after joining Veitch's company in 1934 both he and his new wife were hit by a short illness. Ievers and his wife both have memories of Veitch's kindness to them during that period, as he came to visit them every day during their illness. In 1944 when Ievers was again back in Roorkee and Veitch was Commandant of the Bengal Sappers and Miners, he was kind enough to give Ievers a room in his own bungalow.

VI. RETIREMENT YEARS

On the 15th of November 1953 Veitch was forced to retire from the Army due to ill health. At the time of his retirement he had already returned to the U.K., having departed from Pakistan on the 21st of January 1953. General Veitch subsequently had to undergo serious surgery and suffered a permanent disability which he most gallantly fought until his death. After his retirement from the Army he settled first at Forres and later in the Borders at Tweedside, St. Boswells, Roxburghshire. He made frequent visits to Pakistan after his retirement, where he pursued his fishing and took a very keen interest in sport, particularly athletics, boxing and swimming. There he attended nearly every meeting at which Sapper representatives took part, giving great pleasure and encouragement to the Pakistan Sappers. Returning to Scotland (the Western Isles and Sutherland) in the summer months he made regular fishing trips with Dick Connor, who unfortunately was only to survive his old friend by a few months. Veitch was always a most popular visitor and highly regarded by his many friends in the Western Isles and in Sutherland.

He was a member of the Naval and Military Club and the Punjab (Frontier Force) Club in Lahore (2). The Frontier Force Club, which later became The Punjab Frontier Force Association, was founded in 1931. When it was instituted it was agreed that all Garrison Engineers who had served in agencies with the Frontier Corps were eligible for membership. Veitch qualified for membership in the early 1930s when he was Garrison Engineer of the Wana Road project and continued to pay his Club subscription until 1957 (26). He took great pride in having been accepted as a member of the Frontier Force Club; but what he always considered the crowning honour of his career was his appointment as the first Colonel Commandant of the Pakistan Engineers. His portrait hangs in their Mess at Risalpur, a memorial of his devoted service to the country and the people he loved so well.

Colonel M.B. Adams, Hon. Secretary of King George V's Own Bengal Sappers & Miners Officers Association recalls meeting General Veitch in the early 60's at a Bengal S & M dinner in London (6). Colonel Adams feelings about the General are summed up when he writes.

"There is no doubt that he was a great man and ideal to be Commandant of the Bengal S & M in wartime with the tremendous administrative problems involved. Though he would appear odd with present day standards, he was not at all unusual in the standards of the pre-war Indian Army where individuality such as his was much admired by the Indian Jawans".

Even in his retirement Veitch did not forget his comrades from the Bengal Sappers and Miners. After his retirement from the Army Eyre Ievers, his wife, son and daughter lived in Australia for over 20 years. When Ievers' son died there in 1964, somehow Veitch found out about his friend's loss and sent a cable of sympathy to him. He apparently still had time to think about others in their time of need and sorrow, even though he himself must have been suffering from his own terrible illness.

General Veitch died at Western General Hospital in Edinburgh at 0500 hours on the 13th of December 1969 at the age of 68. The cause of death was listed as pulmonary oedema and left ventricular failure (19). He had previously undergone a pneumonectomy for the removal of his right lung (probably as a result of cancer from cigarette smoking). It was probably as a result of the pneumonectomy that he had been forced to retire from the Army.

General Veitch's death was recorded on the 15th of December 1969 in the District of Melrose, County of Roxburgh (19). His Will was probated at Somerset House in London in the Spring of 1970 (20). Those mentioned in his will include his sister Vera Cecil Veitch, M.B., Ch.B. who was a resident of Belhaven, Ormiston Terrace, Melrose, Borders. Dr. Vera C. Veitch only survived her brother by about four years. She died on the 24th of September 1973.

Francis Paterson Smart and John Archibald Harris, both Solicitors in Melrose, were also mentioned in Veitch's will as Trustees. Mr. Smart must have been more than just a legal advisor to General Veitch as he is listed as a friend and the Informant on the General's death certificate.

Legacies bequeathed by the General included his niece, Miss Helen Cecil Urquhart, then of Heathercroft, Saint Boswells. Miss Urquhart was the daughter of the General's sister Vera who, at the time of her death, was known by her maiden name and not by Urquhart (21). Miss Urquhart was last heard of in 1977 as residing in Bonneville, France (6).

Veitch also remembered his faithful servants in his will. To his friend Zafar Ali Khan of Mardan, West Pakistan he left a sum for his assistance in nursing him through two serious illnesses while in Pakistan. He also remembered his housekeeper, Miss Alice Ballantyne of Floral Bank, Gatton-side, Melrose, for her faithful service.

The Imperial Cancer Research Fund, Lincoln's Inn Fields, London was also mentioned in his will. Further evidence, it would appear, that it was this disease that incapacitated him and forced his retirement from military service, and indirectly was one of the causes of his death.

ENDNOTES:

i. From his own military experience the author recalls that building fronts covered with wire screens were still in vogue in Saigon, South Viet Nam in 1971 as protection against Viet Cong grenades and satchel charges.

ii. Bengal Sapper and Miner officers and men wore dark navy blue hose tops below the knee and were easily distinguished. "Kale half tope” was the typical approximation spoken for these hose - kale meaning black.

iii. Here is another allusion to Veitch's behavior along the lines described by Philip Mason in his book “The Men Who Ruled India".

iv. Veitcho was a nickname by which some of his officers referred to him.

v. During the writing of this biography the medals of Rex Holloway were located by the author in Canada. As a sequel to General Veitch's story the author also plans to write Rex Holloway's biography.

REFERENCES

1. Extract of an Entry in a Register of Births for the Parish of Dunbar, in the County of Haddington, No. 067945 dated 29 April 1988, re: William Lionel Douglas Veitch.

2. Who's Who, 1968-1969. St. Martin's Press, New York, p. 3141.

3. The Edinburgh Academy Register, 1824-1914. Edinburgh Academical Club, Edinburgh, p. 523.

4.

Memoir of Major General William Lionel Douglas Veitch. The Royal

Engineer Journal. The Institution of Royal Engineers, June

1970, pp. 164-166.

5. The Monthly Army List, June

1926. HMSO, London, p. 332a.

6. Adams, Colonel M.B. Letters to Lieutenant Colonel Edward De Santis dated 9 Jan 1988, 1 Feb 1988, 10 Feb 1988, 15 Feb 1988, 3 Mar 1988, 15 Mar 1988, and 31 Mar 1988.

7.

Sandes, Lieutenant Colonel E.W.C. The Military Engineer in

India. Volume I. The Institution of Royal Engineers,

Chatham, Kent.

8. The Monthly Army List, October

1935. HMSO, London.

9. Shaw, Lieutenant Colonel W.A. Letter to Lieutenant Colonel Edward De Santis dated 2 Mar 1988.

10. David, Colonel D.C.S. Letter to Lieutenant Colonel Edward De Santis, dated 26 February 1988, forwarded through Colonel M.B. Adams, 3 Mar 1988.

11. Odell, Major E. Letter to Lieutenant Colonel Edward De Santis dated 18 May 1988.

12.

Masters, J. Bugles and a Tiger. The Viking Press, New

York, 1956, p. 137.

13. Mollo, B. The Indian Army.

New Orchard Editions, Poole, Dorset, 1981.

14.

Greenwood, Brigadier H.R. Letter to Colonel M.B. Adams, dated 8

February 1988.

15. The Quarterly Army List, August 1949,

HMSO, London.

l6. Lawrie, Colonel W.G.A. Letters to

Colonel M.B. Adams and Lieutenant Colonel Edward De Santis, dated 8

February 1988 and 19 March 1988.

17. Ievers, Colonel E.A. Letter to Lieutenant Colonel Edward De Santis dated 25 Jun 1988.

18. Gordon, Major L.L. British Battles and Medals. Spink & Son Ltd., London, 1971.

19. Extract of an Entry in a Register of Deaths in the General Record Office, New Register House, Edinburgh, No. 000293, dated 4 May 1988, re; William Lionel Douglas Veitch

20. Extract of the Will of Major General William Lionel Douglas Veitch, from the Registers of Scotland, 20 March 1970.

21. Black, Graeme. Letter to Lieutenant Colonel Edward De Santis, dated 6 October 1988.

22. Odell, Major E. Letter to Lieutenant Colonel Edward De Santis, dated l4 August 1988.

23. Black, Graeme. Letter to Lieutenant Colonel Edward De Santis, dated 26 July 1988.

24. David, Colonel D.C.S. Comments on the life of Major General W.L.D. Veitch, dated 5 August 1988.

25. Perceval-Price, Colonel M.C. Letter to Colonel M.B. Adams, dated 7 August 1988, forwarded to Lieutenant Colonel Edward De Santis.

26. Taylor, F.W.S. Letter to Colonel M.B. Adams, dated 31 August 1988, forwarded to Lieutenant Colonel Edward De Santis.

27. Feilden, Sir Bernard M. Letter to Colonel M.B. Adams, dated 23 August 1988, forwarded to Lieutenant Colonel Edward De Santis.

28. Rolt, Lieutenant Colonel M.J.J. Letter to Lieutenant Colonel Edward De Santis, dated 24 July 1988.

29.

Barker, Lieutenant Colonel N. Letter to Lieutenant Colonel

Edward De Santis, dated 9 September 1988.

30. Mason,

P. The Men Who Ruled India. Jonathan Cape, London, 1985,

P. 144.

31. Armstrong, Major A.E. More Roads (Waziristan, 1937). The Royal Engineers Journal, Vol. LIII, March 1939. The Institution of Royal Engineers, Chatham, Kent, pp. l-l6.

32. E.-in-C., India. The Corps of Indian Engineers. The Royal Engineers Journal, Vol. LIX, March 1945. The Institution of Royal Engineers, Chatham, Kent, pp. 36-43.

33. E.-in-C., India. Reconstitution of the Army in India. The Royal Engineers Journal, Vol. LXII, March 1948. The Institution of Royal Engineers, Chatham, Kent, pp. 47-51.