Major

HUGH MACLURE HODGART, M.C.

Royal Engineers

By

Lieutenant Colonel (Retired) Edward De

Santis, MSCE, PE, MInstRE

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

(July 2020)

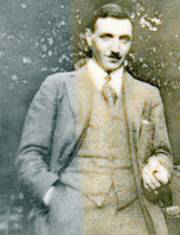

Figure 1.

Major Hugh Maclure Hodgart, R.E.

(Photograph courtesy of the Hodgart family)

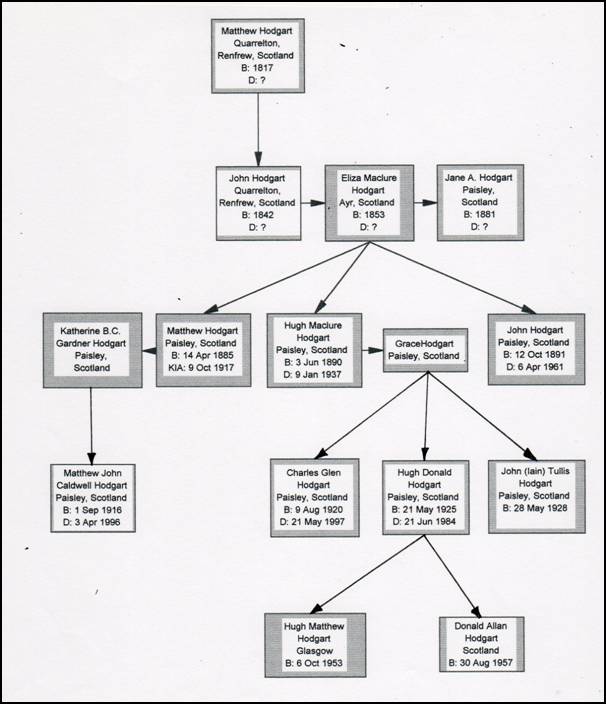

Grandparents

The grandfather of Hugh Maclure Hodgart was Mathew Hodgart (1817-1894). The 1881 Census of Scotland indicates that a Mathew Hodgart was residing in Greatflat Villas on Renfrew Road, Abbey, Renfrew, Scotland. Mathew Hodgart had been born in Quarrelton, Renfrew, Scotland and was 64 years old at the time of the census. He was the head of a household consisting of himself, an unmarried daughter named Jessie, age 28, and his mother in law, Janet Allan, age 92 years. Mathew Hodgart’s occupation was listed as Engine Maker. He had a son named John living near him on Renfrew Road.

Parents

Mathew Hodgart’s son John lived a few doors down on Renfrew Road in Gallowhill Cottage. John Hodgart (1842-1902) had also been born in Quarrelton and was 39 years of age at the time of the census. John’s household consisted of himself, his wife Eliza W. Hodgart, née Maclure (1852-1922), age 28, and their infant daughter Jane Allan Hodgart (1880-1951), age 3 months. John and Eliza had married on the 26th of February 1880 at New Kilpatrick, Dunbartonshire.

Also living in the house at the time was a visitor named Margaret Reid, age 62, of Glasgow. The Hodgarts had two servants; Jeannie C. Mowatt, age 28, of Deemers, Orkney, Scotland, and an English girl, Jane Marland, age 17. John Hodgart’s occupation at the time of the 1881 census was listed as Master Engine Maker.

John Hodgart died in Paisley, Renfrewshire on the 28th of

November 1902. Eliza Hodgart died on

the 8th of October 1922, also in Paisley.

Siblings

In addition to their daughter Jane, John and Eliza Hodgart went on to have three sons. Hugh Maclure Hodgart (1890-1937), the main subject of this research work, was born at Linnsburn, Renfrew Road in Paisley, Scotland, on the 3rd of June 1890. He was their second son.[1] At the time of Hugh’s birth, the Hodgarts already had one son, Matthew (1885-1917), who was born on the 14th of April 1885.[2] The Hodgart’s third son, John (1891-1961), was born on the 12th of October 1891.[3]

Education

Merchiston Castle School in Edinburgh was to figure prominently in the lives of the Hodgart boys. Matthew entered the school as a Boarder in the third (October) term of 1898 and left in 1902. He went to work as a mechanical engineer for Fullerton, Hodgart & Barclay Limited in Paisley[4],[5],[6]. Matthew appears to have married sometime between leaving Merchiston Castle School and the start of the Great War in 1914. His wife was Katherine B.C. Gardner.

Hugh entered Merchiston Castle Preparatory School in 1902 and his younger brother John followed him in 1903. Hugh then entered the school as a Boarder in the third (October) term of 1904 and John followed him the next year entering as a Boarder in the third (October) term of 1905.[7],[8]

When Hugh graduated from Merchiston Castle School in July of 1907 he went

to work for the Vulcan Engine Works[9]

in Paisley as an Ironfounder. His address after graduation was Westerley,

Paisley, Scotland. It would appear

that he was following in the footsteps of both his father and his grandfather,

both of whom were Engine Makers. Hugh’s

brother John graduated in July of the following year, listing his profession as

engineer. John’s address following

graduation was 5 Craigfaulds Avenue, Paisley, Scotland.[10],[11]

Figure

2. Merchiston Castle School,

Edinburgh.

(Photograph courtesy of Wikipedia)

3.

COMMISSIONING AND ACTIVE SERVICE

Pre-War Service

Hugh Maclure Hodgart was commissioned a 2nd Lieutenant in the Royal Engineers (Territorial Force) on the 2nd of February 1911. He was posted to the Renfrewshire (Fortress) Works Company, R.E. His older brother Matthew was also serving in this company at the time.

On the 3rd of February 1911 Hugh was promoted to the rank of Lieutenant in the Renfrewshire (Fortress) Works Company, R.E. He was stationed at the time at Fort Matilda in Greenock, Scotland.[12] Fort Matilda originally housed a coastal battery built on Whiteforeland Point in 1814–1819 to defend the River Clyde before it became the headquarters of the company.

On the 21st of January 1914 Hugh was promoted to the rank of Captain and was serving with the 1st (Renfrew) Field Company, R.E., a company of the Lowland Division. By April of 1914 he was commanding No. 1 (Works) Company, Renfrewshire Fortress Engineers at Paisley.[13]

Service in the

Great War

Captain Hugh Maclure Hodgart’s company was mobilized on the 4th of August 1914, the very first day of the start of the Great War of 1914-1918. On the 26th of August 1914 his younger brother John was commissioned a 2nd Lieutenant in the Royal Field Artillery and was posted to the 3rd Highland (Howitzer) Brigade Ammunition Column at Cathcart, a town located about 3 miles due south of Glasgow.[14] Hugh’s brother Matthew was promoted to the rank of Captain on the 12th of October 1914 and was serving with No. 1 (Works) Company, City of Edinburgh Fortress Engineers with headquarters at 28 York Place in Edinburgh.[15] By April of 1915, Captain Matthew Hodgart had transferred and was serving in No. 1 (Works) Company, Renfrewshire Fortress Engineers at Paisley along with his brother Hugh.[16]

|

|

(Photograph courtesy of Google Earth) |

Service in

Egypt

On the 6th of June 1915, Captain Hugh Maclure Hodgart was appointed Second in Command of the newly formed 1/1st Renfrewshire Field Company, R.E. (T). He embarked for the Egyptian Expeditionary Force on the 10th of December 1915 in temporary command of the company. The company arrived at El Kubri, Egypt on the 15th of January 1916 and was immediately attached to the 10th Indian Division for work in the El Kubri – Es Shatt area just north of the city of Suez at the inlet to the Gulf of Suez.

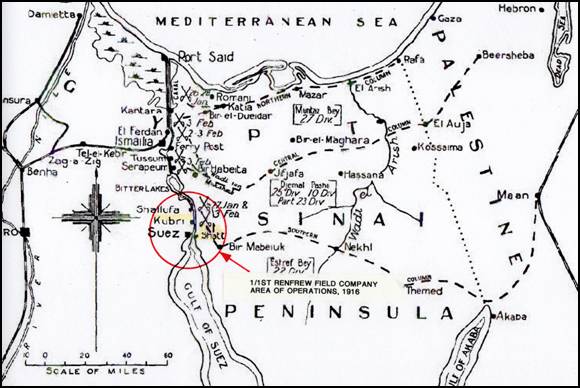

Figure

4. The Sinai Peninsula and the Gulf

of Suez.

(Map courtesy of the Australian Light Horse Studies Centre)

The 10th Indian Division (two brigades only) was already on the canal with its single field company of engineers when it was augmented by the 1/1st Renfrewshire Field Company and the 1/1st City of Edinburgh Field Company. The former left a detachment at El Kubri and moved to Ayun Musa on the 19th of January. The company worked on the canal defences, water supply and the light railway from Quarantine upon its arrival at Ayun Musa. The 1/1st City of Edinburgh Field Company, one of the few engineer units to be over establishment, began an outpost line for one and a half battalions astride the track to Nekhl.

In the 10th Indian Division’s sub-section of the canal defence system, the 1/1st Renfrewshire Field Company continued work on the defences in the rocky ground near Ayun Musa, and on water supply and light railway work right into March of 1916. Captain Hugh Hodgart had relinquished temporary command of the company to Lieutenant Colonel A.H. Anderson, R.E. on the 5th of February 1916. On the 4th of March, when Lieutenant Colonel Anderson was appointed Commander Royal Engineers (CRE) of the 10th Indian Division, Hugh Hodgart resumed command of the company.

On the 8th of March 1916 the 1/1st Renfrewshire Field Company moved to Esh Shatt to lay light railways, install water storage facilities in the forward defence posts and to construct defences there and at the Quarantine bridgehead. On the 12th of March the company was detached from the 10th Indian Division. Major Charles Hordern assumed command of the company on the 12th of April 1916 and once again Captain Hugh Hodgart took up the position as Second in Command. Shortly after this change of command, the company received orders to leave Egypt for the Western Front in Europe. The company embarked at Alexandria on the 17th of April 1916 bound for France and Flanders. The unit strength at that time was 6 Officers, 231 Other Ranks, 8 animals and 21 vehicles.[17] The company had suffered no casualties while serving in Egypt.[18]

Service in

France and Flanders

When the company disembarked at Marseilles on the 23rd of April 1916, Captain Hodgart was ill and was admitted to hospital.[19] The company had already joined the British 4th Division on the 2nd of May. He rejoined the company on the 12th of May. On the 1st of June 1916, Hugh’s brother John was promoted to the rank of Lieutenant in the Royal Field Artillery.[20]

Captain Hodgart’s company arrived on the Western Front in time to participate in the bloody battle of the Somme with the 4th Division. This battle commenced and the 1st of July 1916 and lasted until the 13th of July. The 4th Division was a Regular Army formation, part of the original British Expeditionary Force, and had been serving on the Western Front since August of 1914. The Commander Royal Engineers of the 4th Division was Lieutenant Colonel S. Mildred, R.E.[21] In addition to Hodgart’s company, Mildred also had the 9th Field Company and the 1/1st Durham Field Company under his command.

Under orders issued by VIII Corps, the divisional Royal Engineers were not intended to take part in the initial assault on the 1st of July; however, one section of sappers was placed at the disposal of the commander of each assaulting brigade. The engineers were not to be ordered forward until the objective had been gained. The remainder of the Royal Engineers were held back to work on improving forward roads and water supply and then to consolidate strong points at night, assuming that objectives had been taken and that there were strong points to consolidate. The division sustained disastrous losses in its assault; although the leading troops penetrated the strong point known as “The Quadrilateral,” the following waves came under heavy fire. Under cover of darkness, the battle front was cleared – the engineers assisting in bringing in the wounded – and defences were re-organised, but the Quadrilateral had to be abandoned the following morning. Major Hordern was admitted to hospital[22] on the 6th of July in the middle of the Somme battle and Captain Hodgart assumed command of the company. Although few engineer soldiers went forward with the assaulting infantry, Hodgart’s company suffered two men killed in action; 1082 Staff Sergeant Peter Lyon and 1115 Sapper William Hamilton.[23]

The 4th Division went back into action later in the Somme offensive, at the Battle of the Transloy Ridges, with little better success. Hodgart again assumed command of the unit, now known as the 1st (Renfrew) Field Company, R.E. On the 6th of August 1916, Hugh Maclure Hodgart was promoted to the rank of Temporary Major.[24]

Major Hodgart commanded the company through the battle of Le Transloy

from the 1st to the 18th of October 1916 with the 4th

Division under the control of the XIV Corps.

The battle was fought during a period of terrible

weather in which the heavy, clinging, chalky Somme mud and the freezing, flooded

battlefield became as formidable an enemy as the Germans. The British gradually

pressed forward, still fighting against numerous counter-attacks, in an effort

to have the front line on higher ground from which the offensive could be

renewed in 1917. Heartened by the

occupation of much of the Thiepval Ridge, General Haig determined to continue

large-scale offensive operations into the autumn.

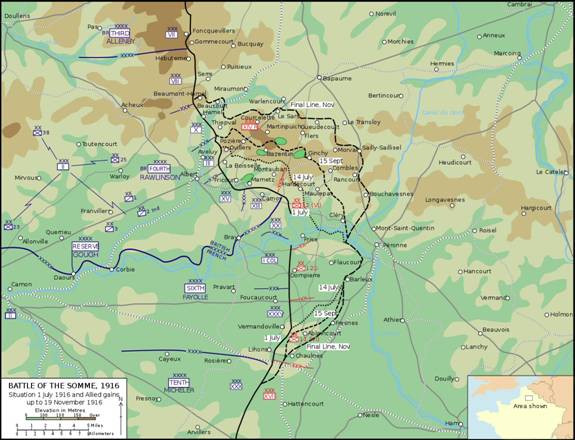

Figure

5. The Battle of Le Transloy, 1 to

18 October 1916.

(Map courtesy of Wikipedia)

The Battle of the Transloy Ridges represented Fourth Army's part in this

grand design, and its costly attacks were intended to coincide with simultaneous

advances by the Reserve Army planned for early October.

The fighting took place during worsening weather and dreadful battlefield

conditions. Fourth Army's objectives necessitated, as a preliminary, the taking

of Eaucourt L'Abbaye and an advance on III Corps entire front was launched,

after a seven-hour bombardment, at 3.15pm on the 1st of October. The

attack met fierce German resistance and it was not until the afternoon of the 3rd

of October that the objectives were secured. Rawlinson’s follow-up attack was

delayed by atrocious weather. Starting at 1.45pm on the 7th of

October the advance involved six divisions and resulted in heavy British

casualties and little success except for 23rd Division's capture of Le Sars.

Continuous rain during the night hampered the removal of casualties and further

forward moves. The failure to secure original battle objectives led to a renewed

major assault on the afternoon of the 12th of October when the

4th Division on the right of XIV Corps attacked with the 10th Brigade next to

the French 18th Division (IX Corps). The

attack floundered towards German trench lines in front of

Le Transloy, while formations on the left slogged towards the Butte de

Warlencourt. Despite the slightest of gains (measured in hard fought for trench

yards) the operation was not successful. Orders

for a fresh attack, issued late on the 13th of October, ignored the

desperate conditions and physical state of the attacking troops.

On the 14th of October, the XIV Corps attempted a

surprise attack at 6:30 p.m. with the 2nd Seaforths

of the 4th Division, which got into Rainy Trench and gun-pits south of Dewdrop

Trench and were then forced out by a counter-attack. The

subsequent early morning assault on the 18th of October (well before

daylight) witnessed heroic efforts to advance but minimal gains were made

against resolute defenders well supported by accurate artillery fire.[25]

Given the terrible weather conditions during this battle and the Somme

mud and flooded battlefield, the divisional engineers must have exerted

considerable effort to assist the movement of the infantry during their attacks.

Hugh Maclure Hodgart was promoted to the substantive rank of Major on the 20th of December 1916. The 1st (Renfrew) Field Company, R.E. was redesignated the 406th (Renfrew) Field Company, R.E. in January of 1917. While Hodgart commanded the company during the winter of 1916/1917, he lost one man to enemy action. 420084 Sapper John Faulkner was killed in action on the 14th of January 1917. Despite the heavy fighting during the Battle of Le Transloy the company suffered no fatalities during that period. Sapper Faulkner’s death probably was due to a sniper or artillery fire.

Home Service

Major Hugh Maclure Hodgart returned home on the 27th of March 1917 and did not return to active service for the remainder of the war. On the 15th of April 1917 he was assigned to the Territorial Force Reserve in the rank of Major. On the 18th of May 1917 the London Gazette published a mention in despatches for Major Hodgart citing his good works while on active service with his company.

All the while that Hugh was serving at home the war was still raging in France and Flanders. His brother John was awarded the Military Cross on the 25th of August 1917 for his distinguished service with the Royal Field Artillery.[26] Sadly, all was not good news. Hugh was to learn that his older brother Matthew was killed in action on the 9th of October 1917 near Ypres during the battle of Broodseinde while in command of the 406th Field Company. Two of Matthew’s men, 420136 Sapper William Laing and 420162 Sapper William McMillen, were killed on the same day.[27] The men were killed in the Battle of Poelcappelle.

The Battle of Poelcappelle was fought by the British Second Army and Fifth Army against the German 4th Army. The battle marked the end of the string of highly successful British attacks in late September and early October, during the Third Battle of Ypres. Only the supporting attack in the north achieved a substantial advance. On the main front the German defences withstood the limited amount of artillery fire achieved by the British after the attack of the 4th of October. The ground along the main ridges had been severely damaged by shelling and rapidly deteriorated in the rains, which began again on 3 October, turning some areas back into swamps. Dreadful ground conditions had more effect on the British, who needed to move large amounts of artillery and ammunition to support the next attack. The battle was a defensive success for the 4th Army, although costly to both sides. The weather and ground conditions put severe strain on all the infantry involved and led to many wounded being stranded on the battlefield.

Major Hodgart and his company would be involved in repairing such damage

to make movement by infantry, artillery, field ambulances and supply vehicles

possible. This work surely was done

under sniper and artillery fire, as usual. Matthew

Hodgart fell victim to enemy action during this battle.

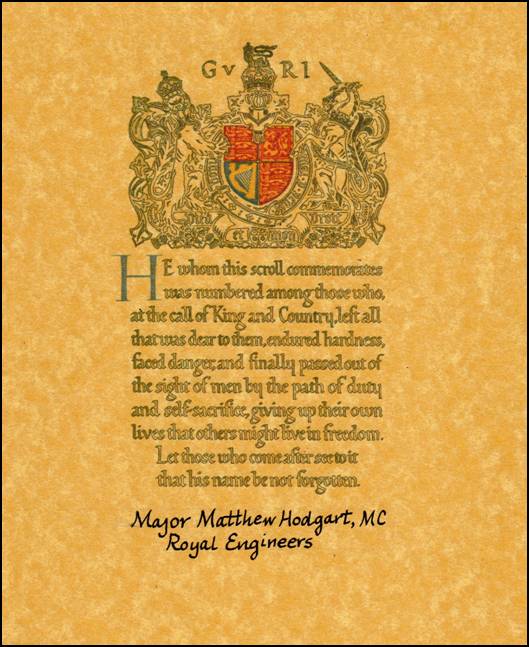

He was awarded the Military Cross, posthumously, on the 1st of

January 1918. He also received a

mention in despatches.[28]

Matthew was buried at Bard Cottage Cemetery, Boezinge, Ypres, West-Vlaanderen,

Belgium, Plot V, Row A, Grave 11. At

the time of his death, Matthew’s wife Katherine was living at Graewraes,

Paisley (see Addendum No. 3).

4.

AWARDS AND DECORATIONS

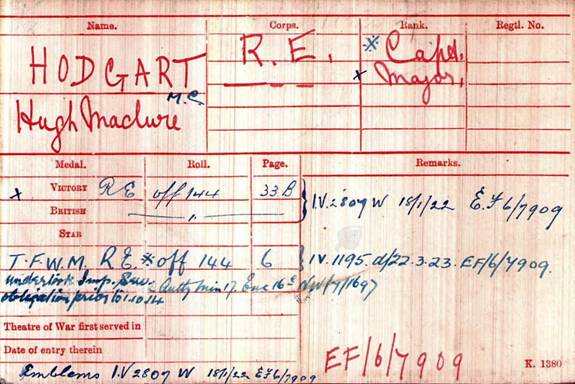

For his service during the war, Major Hugh Maclure Hodgart was awarded the British War Medal, Victory Medal with mention in despatches, and the Territorial Force War Medal. He also received the Special Constabulary Long Service Medal[29] and is thought to have been awarded the Military Cross as well, although this latter medal cannot be verified by a citation in the London Gazette.[30]

Family historians claim that Hugh was awarded the Military Cross for his service, but the author’s has found no official evidence that he did. The Military Cross in the photograph below is a tailor’s specimen. It was added to the group of original medals by the author. Although no London Gazette citation for the Military Cross could be found, indications that he received the award have been found in other non-official publications (see Endnote 30). There is also a notation on his Medal Index Card (see Figure 7 below) indicating that he had been awarded the “M.C.”

Figure

6. The Medals of Major Hugh Maclure

Hodgart, R.E.

(Photograph from the author’s collection)

Figure

7. The Medal Index Card of Major

Hugh Maclure Hodgart, R.E.

(Image courtesy of Ancestry.com)

5.

POST WAR SERVICE AND CIVILIAN LIFE

John Hodgart continued to serve after the Great War and was promoted to the rank of Captain in the Royal Field Artillery on the 11th of March 1919.[31] Hugh was still serving as a Major with the Renfrewshire Fortress Engineers, Territorial Force Reserve in Paisley as late as December of 1920.[32]

Hugh Maclure Hodgart married Grace McGowan Glen (1898-1972) in 1919 at Hillhead, Ayrshire. Grace had their first son, Charles Glen (1920-1997), on the 9th of August 1920, and their second child, another son named Hugh Donald (1925-1984), was born on the 21st of May 1925. It appears that after the war, Hugh went to work for his father’s firm of Fullerton, Hodgart and Barclay Ltd. and eventually rose to be one of the managing directors of the firm.[33]

Figure

8. Hugh Maclure Hodgart, c. 1920.

(Photograph courtesy of the Hodgart family)

By June of 1926, Hugh’s brother John had transferred to the Royal Engineers and was serving with the 51st Highland Divisional Engineers at Hardgate in Aberdeen, Scotland. At this time he was also the Secretary of the local Territorial Army Association Branch.[34]

Hugh’s third son, John (Iain) Tullis, was born on the 28th of May 1928. His son Charles entered Merchiston Castle School as a Boarder in the third (October) term of 1933 just as his father and his uncles had done before him. Charles was a Junior Prefect and was awarded colours with the Shooting VIII after 2 years of participation. He was also a member of the school’s running team.[35]

In the meantime, Hugh’s brother John was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel in the Royal Engineers (T.A.) on the 21st of December 1931 and was appointed Commander Royal Engineers of the 51st (Highland) Division.[36],[37] In October of 1935 John Hodgart was still serving as the CRE, 51st (Highland) Divisional Engineers with headquarters at the Drill Hall, 80 Hardgate in Aberdeen. In addition to the Military Cross, he had already been awarded the Territorial Decoration by this time.[38],[39] About this time, John Hodgart retired as a Brevet Colonel, Territorial Army Reserve of Officers.[40]

Hugh Maclure Hodgart died of Hodgkins Disease on the 9th of January 1937 at the age of 47.[41] He was a man of many talents, a writer of poetry and a keen photographer who developed his own pictures. It appears that he was also fond of mountaineering and was an avid golfer. Hugh was Captain of the Ranfurly Golf Club from 1934 to 1935.

Although Hugh Maclure Hodgart’s death ends the tale of the primary character of this research, the Hodgart family continued to serve King and Country, and the remainder of their story is certainly worth telling.

Further

Services of the Hodgart Family

In 1937 Hugh’s son Hugh Donald entered Merchiston Castle School as a Boarder in the Summer term. He became a Senior Prefect, won a jersey with the First Football XV and colours for 2 years of participation with the Shooting VIII].[42] Charles graduated from the School in July of 1937 and became a Justice of the Peace in 1960.[43]

At the start of the Second World War in 1939, John Hodgart was called back to the Colours and was re-employed as a Major in the Royal Engineers. During the period from 1941 to 1944, John commanded No. 6 and No. 3 Bomb Disposal Companies, R.E.,[44] one of the most dangerous assignments that any man could have during the war. During the Second World War the men of the Royal Engineer Bomb Disposal (BD) Companies risked their lives almost every day, often without ever leaving the shores of Britain. Some 45,000 unexploded enemy bombs (UXBs), as well as 7,000 live anti-aircraft shells and 300,000 beach mines were made safe. In all 394 BD officers and other ranks were killed, and more than 200 were wounded, mostly in the early years of the war when disposal techniques were in their infancy and developed by an often deadly process of trial and error. An officer who served in No. 3 Bomb Disposal Company was Lieutenant Eric Wakeling, with whom the author corresponded over many years.[45]

Figure

9. Lieutenant Eric Wakeling, R.E.

(Photograph courtesy of The Telegraph)

In October of 1939, Hugh Maclure Hodgart’s son John Tullis entered Merchiston Castle School as a Boarder in the third term, thus upholding the family tradition.[46] In 1943 Hugh Donald Hodgart graduated Merchiston Castle School and enlisted in the Royal Navy Volunteer Reserve. During the remainder of the war he served as an Able-Bodied Torpedoman and was discharged in 1945.[47]

During 1944 John Hodgart was re-granted the rank of Brevet Colonel in the Territorial Reserve of Officers and John Tullis Hodgart graduated from Merchiston Castle School. Of all the members of the Hodgart family, John Tullis Hodgart was the only one not to serve with the Forces.

Charles Glen Hodgart was commissioned a 2nd Lieutenant in the Royal Engineers (T.A.) in 1938. He served during the war in North Africa, Egypt, and Italy, and in Greece from 1952 until 1960. He was awarded the Territorial Decoration for his service.[48] In 1953 Charles was elected an Associate Member of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers and in 1954 he became the Managing Director of Fullerton, Hodgart & Barclay, Ltd. In 1954, Charles also became the Director of Maitlands (Iron Founders), Ltd.

In September of 1956 Charles, then a Lieutenant Colonel, assumed command

of 102 Corps Engineer Regiment at Paisley. At

that time the regiment was composed of the following units:[49]

238 Corps Field Park Squadron

276 Field Squadron

279 Field Squadron

540 Field

Squadron

In 1960 Charles was still serving as the Commanding Officer, 102 Corps Engineer Regiment. From 1960 to 1961 he served as Deacon of the Incorporation of Skinners, and in 1961 he was elected President of the Paisley Branch of the British Legion. From 1961 to 1962 Charles served as Captain of the Ranfurly Castle Golf Club.

John Hodgart died in Paisley on the 6th of April 1961.

The family lineage was carried on by the sons of Hugh Maclure Hodgart.

The following data was available on the brothers as of 2005:

Charles Glen Hodgart (1920-1997)

was Colonel County Commandant, Renfrewshire and Bute A.C.F. and Deputy

Lieutenant of Renfrewshire. His

address in 1962 was Sunnylaw, Brediland Road, Paisley.

He was married and had three daughters.

Hugh Donald Hodgart (1925-1984)

was the Managing Director of Maitlands (Ironfounders) Ltd. and Director of

Fullerton, Hodgart & Barclay Ltd. His

address in 1962 was Fore House, 27 Park Road, Paisley.

He was married at this time. He

died on the 21st of June 1984.

John Tullis Hodgart (1928-2005)

was Managing Director of Charles E. Hart, Ltd., Engineers’ Agents.

His address in 1962 was 2A Craigfaulds Avenue, Meikleriggs, Paisley.

He too was married.

By 1977 Charles Glen Hodgart had become the Managing Director of Fullerton, Hodgart & Barclay Ltd. in place of his brother Hugh. As of March of 1977 the firm was located on Renfrew Road in Paisley, but the firm ceased to exist shortly thereafter due to liquidation.[50] Charles was still living at his former address in 1977. He died on the 21st of May 1997.

In the year 2000 the Hodgart lineage was still being carried forward by Hugh Maclure Hodgart’s grandson, Hugh Hodgart, of Bearsden, Glasgow.

Figure

10. The Hodgart Family Tree.

(Image prepared by the author)

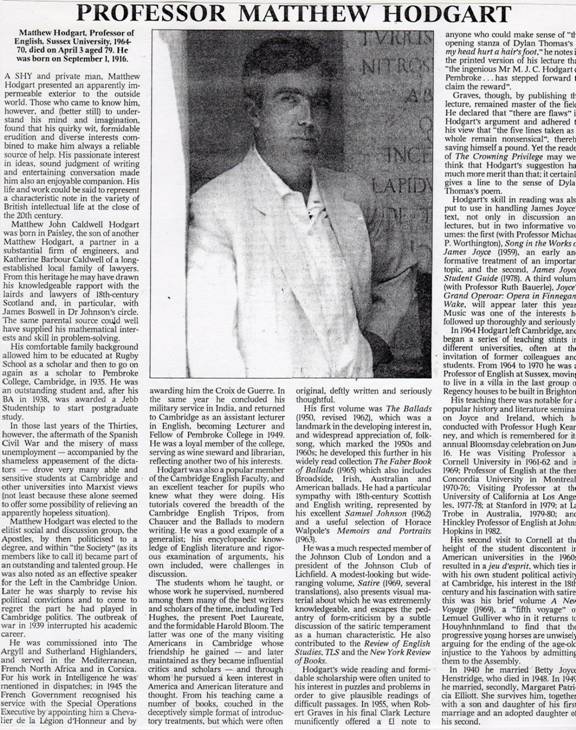

ADDENDUM

NO. 2

The information in this Addendum was kindly provided in December of 2002

by Matthew Stephen Hodgart of Guildford, Surrey.

The information adds much to the Hodgart family history.

Matthew Stephen Hodgart goes by the name Stephen and is referred to by

that name in this Addendum. NOTE:

Stephen Hodgart provided the information in presented in plain text.

Information in italics was

taken from Who's Who, 1983.

Hugh Maclure Hodgart, the primary subject of this research, was Stephen

Hodgart's great uncle. Stephen

Hodgart's father was Matthew John Caldwell Hodgart who was the only son of

Hugh's elder brother Major Matthew Hodgart, MC, R.E.

According to Stephen, photographs of Hugh and his brother Matthew show

them to be remarkably similar in appearance, so much so that they almost could

have passed for twins.

Stephen Hodgart's grandmother was Katharine Barbour Caldwell (née

Gardner). She came from a long

established family of Paisley lawyers. His

father was born on the 1st of September 1916.

He had a brief but interesting military career and a longer, rather

distinguished academic career, which rated a four-column obituary in the London

Times when he died on the 3rd of April 1996 at the age of 79.

According to Stephen and the London Times obituary, Matthew John Caldwell

Hodgart was a shy and private man. He

was never at ease with people who did not have his level of IQ and encyclopedic

knowledge, for he had a formidable memory and very fast reasoning powers.

In the right circumstances his conversation was stimulating and

informative. He was an excellent

teacher, especially to those students who knew what they were doing and were

willing to learn.

Stephen's grandmother Katharine was a beautiful young war widow who

wanted the best available education for her clever son.

She did not believe that he could get the quality of education she

desired for him in Scotland, so she sent him to Rugby, one of the famous English

public schools. While at Rugby,

Matthew earned a scholarship to Pembroke College at the University of Cambridge.

Matthew was a brilliant student at Pembroke College and was invited to

join the famous "secret society" of so-called Apostles consisting of

an elite group of intellectuals. He

graduated with a Bachelor of Arts Degree in 1938 (Jebb Studentship 1938-1939).

During the Second World War Matthew, like so many of the Hodgarts before

him, served in the Army. He joined

the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders at the outbreak of the war in 1939, but at

some point during the war he abandoned regimental soldiering to serve in the

Intelligence Corps and then in the Special Operations Executive (SOE).

Because of the covert nature of SOE operations during the war, Matthew

was always reticent about the details of his time in the military.

The nature of SOE operations required him to receive training in

sabotage, explosives and demolitions, secret codes, weapons training and other

combat skills. These "core

skills" for SOE operatives had to be rapidly taught to aspiring agents.

In addition to learning these skills, he eventually taught them to other

men and once told his son that he quite enjoyed being a "Professor of

Terrorism." His military

qualifications therefore were quite the opposite of his Uncle Hugh's

qualifications. Rather than building

things, Matthew Hodgart was in the business of blowing things up.

For his war service, Matthew John Caldwell Hodgart was mentioned in

despatches, appointed a Chevalier de la Légion d'honneur and also was awarded

the French Croix de Guerre in 1945. He

spoke excellent French and served in North Africa and Corsica during the early

part of the war and finished the war in India with the rank of Major.

Stephen could never extract from his father an intelligible account of

what he did in North Africa or in India.

While in North Africa, Matthew Hodgart met and drank a few beers with

Hugh Maclure Hodgart's son Charles (1920-1997), who was always known to him as

"Cousin Charlie." Matthew

enjoyed his food and wine, but always kept his drinking under control.

This undoubtedly was a good thing, since too much drinking would not have

been conducive to service in the SOE where secret activities were the trademark

of their operations.

Matthew Hodgart returned to Pembroke College after the war and earned a

Masters of Arts Degree in 1945. He then resumed his academic career as an Assistant Lecturer in English

from 1945 to 1949. He was

appointed a Fellow of Pembroke College in 1949 and held

the position of Lecturer in English until 1964 when he sought and found

promotion as Professor of English to the then new Sussex University.

While at Sussex University he also

was a Visiting Professor at Cornell University in New York State (1961-1962

and 1969).

He retired from Sussex University in 1970 and became a Visiting

Professor, working on yearly appointments at Concordia University in Montreal (1970-1976),

the University of California in Los Angeles (1977-1978),

Stanford University in California (1979),

La Trobe University) in Australia (1979-1980)

and finally at the Johns Hopkins University (Hinckley Professor) in Baltimore,

Maryland (1982).

He ended his days in his very beautiful Regency house in Brighton, East

Sussex. He was survived by his

second wife who is still living in the house.(+)

Matthew Hodgart never became a public figure himself, but his friends and

pupils were well known in the arts, in the academic world and in political

circles. Among these were poets,

writers, broadcasters, journalists, satirists and other intellectuals, including

the smarter politicians who were with him at Cambridge.

Among his many famous acquaintances were the writer Kingsley Amis, the

British Poet Laureate Ted Hughes, and Abba Eban the Foreign Minister for Israel.

His recreations included travel,

music and photography.

Hodgart published many books, some of which are still in print and are

popular teaching texts. His first

book on ballads is still reckoned to be a classic piece of research.

He was, among other things, an expert on Samuel Johnson and James Joyce.

The following is a list of his

publications:

The Ballads, 1950

Song in the Works of James Joyce, 1959 (with Professor M. Worthington)

Samuel Johnson, 1962

(Editor) Horace Walpole Memoirs, 1963

(Editor) Faber Book of Ballads, 1965

Satire, 1969 (translated into various languages)

A New Voyage, 1969 (fiction)

James Joyce, Student Guide, 1978

Contributing author to the Review of English Studies and Times Literary

Studies

Matthew John Caldwell Hodgart married Betty

Joyce Henstridge in 1940. They

had two children; Matthew Stephen Hodgart, born in 1943 and Jane Katharine

Hodgart, who was born in 1947. Both

grew up as children in Cambridge. Jane

still lives in Cambridge. Stephen is

married and lives in Guildford, Surrey. He

has no children.

Betty Joyce Hodgart died in 1948 and Mathew John Caldwell Hodgart married

Margaret Patricia Elliott in 1949. They

had one adopted daughter.

Stephen continued the Hodgart family tradition by becoming an electrical engineer. He worked on military electronics systems for Marconi-GEC and currently is an academic, being a Reader in Electronic Engineering at the University of Surrey. He was appointed Visiting Professor to the Electrical Engineering Department of the University of Cape Town in the 1990s. Stephen includes among his professional interests the tracking and guidance mathematics of Earth satellites. His hobbies include playing jazz piano and philosophy.

In Memory of

Major MATTHEW HODGART, MC

Died 9 October 1917

Aged 32

406th (Renfrew) Field Coy.

Royal Engineers

Figure 11.

Memorial Scroll to Major Matthew Hodgart, MC, R.E.

(Scroll created by the author from Soldiers Died in the Great War CD)

ADDENDUM

NO. 4

Figure

12. Obituary of Matthew John

Caldwell Hodgart, the Son of Major Matthew Hodgart and Nephew of Hugh Maclure

Hodgart.

(Image courtesy of the Hodgart family)

REFERENCES:

Army Lists

1. Monthly Army List, December 1912.

2. Monthly Army List, April 1914.

3. Monthly Army List, February 1915.

4. Monthly Army List, April 1915.

5. Monthly Army List, June 1919.

6. Monthly Army List, December 1920.

7. Monthly Army List, June 1926.

8.

Monthly Army List, October 1935.

Books

1. HMSO. Army Honours and Awards. J.B. Hayward & Son, London, 197_.

2. MURRAY, A. Sir Archibald Murray’s Despatches (June 1916 – June 1917). J.M. Dent & Sons Ltd., London and Toronto, 1920.

3. Merchiston Castle School Register, 1833 to 1929. H. & J. Pillans & Wilson, Edinburgh, 1929.

INSTITUTION

OF ROYAL ENGINEERS. The History of the Corps of Royal Engineers.

Volume V. The Institution

of Royal Engineers, Chatham, Kent, 1952.

5. History of the Corps of Royal Engineers, Volume VI: Gallipoli, Macedonia, Egypt and Palestine, 1914-1918. The Institution of Royal Engineers, Chatham, Kent, 1952.

6.

University of London War List, 1914-1918, p. 108.

Census

1. 1881 British Census. Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, Family History Library Film 0203584, GRO Reference Volume 573, Enumeration District 81, page 2. Copyright 1999 by Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

2. 1891 Census of Scotland.

3.

1901 Census of Scotland.

Commonwealth

War Graves Commission

1. Memorial to Major Matthew Hodgart, R.E.

2.

Memorial Scroll, Major Matthew Hodgart, R.E.

Correspondence

1. Letter dated 3 June 1977 from Mr. I.V. Balfour-Paul, Merchiston Castle School, Edinburgh, to Lt. Col. E. De Santis.

2. Letter dated 31 May 1977 from Mr. C.G. Hodgart, Fullerton, Hodgart & Barclay Ltd., to Lt. Col. E. De Santis.

3. Letter dated 22 March 1977 from C.G. Hodgart to Lt. Col. E. De Santis.

4. Letter dated 29 June 1977 from C.G. Hodgart to Lt. Col. E. De Santis.

5. E-mail message from Hugh Hodgart of Bearsden, Glasgow, dated 31 May 2000.

Documents

Glasgow University Archives

& Business Records Centre, Archival Authority Records, Glasgow, Scotland,

1999.

Internet

Web Sites

1. Ancestry.com: Various Hodgart Family Trees.

2.

Australian Light Horse Studies Centre.

3. The Great War 1914-1918 'The Rage Of

Men.' TheGreatWar191418

Community.

4.

The Telegraph: Eric Wakeling Obituary.

London

Gazette

1. The London Gazette, 21 April 1911, p. 3096.

2. Supplement to the London Gazette, 25 June 1917, p. 6283.

3. Supplement to the London Gazette, 21 December 1916, p. 12468.

4. Supplement to the London Gazette, 23 August 1917, p. 8684.

5. Supplement to the London Gazette, 25 August 1917.

6. Supplement to the London Gazette, 1 January 1918, p. 38.

7.

Supplement to the London Gazette, 9 March 1918, p. 3076.

Medal

Rolls and Index Cards

1. Medal Index Card, Major Hugh Maclure Hodgart, R.E.

2. Medal Index Card, Major Matthew Hodgart, R.E.

3. Medal Card, Mention in Despatches, Captain H.McC Hodgart.

4. Royal Engineers Medal Roll, British War Medal and Victory Medal, Major H.M. Hodgart.

5. Royal Engineers Medal Roll, British War Medal and Victory Medal, Major M. Hodgart.

6. Royal Engineers Medal Roll, Territorial Force War Medal, Captain H.M. Hodgart.

7.

Effects of Deceased Officer, Major Matthew Hodgart, R.E.

Passenger

Lists

1. S.S. Cameronia, Glasgow to New York, 6 October 1912.

2. S.S. Armadale Castle, Southampton to South Africa, 6 March 1936.

3. S.S.

Arundel Castle, Durban, South Africa to Southampton, 4 May 1936.

Periodicals

The Sapper,

November 1956.

Probate

Calendars

1. Eliza Maclure Hodgart, 8 October 1922, page H 45.

2. Matthew Hodgart, 9 October 1917, p. H 46.

ENDNOTES

[1] Commonwealth War Graves Commission Register No. 440257.

[2] Merchiston Castle School Register, p. 174.

[3] Ibid., p. 201.

[4]

The firm of Fullerton, Hodgart & Barclay

Ltd. originally was established in 1838 as Fullerton & Craig, engineers

in Paisley. The firm existed

under this name until 1920 as a partnership.

The firm specialized chiefly in the construction of mine winding

equipment, compressors, coolers and evaporators.

In 1920 the firm’s name was changed to Fullerton, Hodgart &

Barclay, Ltd., engineers. The

firm was still located in Paisley. Charles

Glen Hodgart appears to have been the directors of the new corporation.

It existed under this name until 1977 as a limited liability

corporation and continued to specialize in the type of equipment previously

mentioned. In 1977 the firm’s

mailing address was:

Fullerton, Hodgart

& Barclay Ltd.

Telegrams:

“Vulcan, Paisley”

P.O. Box No. 10

Telephones:

041-889-2163/4/5

Vulcan Works

Telex:

779297

Paisley PA3 4BE

Scotland

The Directors of the

firm in 1977 were listed as the following:

Charles Glen Hodgart, T.D., D.L., C.Eng., F.I.Mech.E., J.P.

Hugh Donald Hodgart

Ian Tullis Hodgart

B.E. Shaw, B.Sc(Eng), C.Eng., M.I.E.E.

M.C. Rodger, C.Eng., M.I.Prod.E.

The firm apparently ceased to exist in 1977 due to financial and/or legal problems.

[5] Glasgow University Archives & Business Records, Repository Code : GB 248. GB 0248 C0026, 24 October 1999.

[6] Letter dated 31 May 1977 from Mr, C.G. Hodgart, Fullerton, Hodgart & Barclay Ltd. to the author.

[7] Merchiston Castle School Register, p. 197.

[8] Ibid., p. 201.

[9] This works was founded in 1838, and became Paisley's largest engineering works. The foundry was on the west side of Renfrew Road, and the machine and erecting shops on the east. The owners were Fullerton, Hodgart and Barclay. Fullerton, Hodgart and Barclay made a wide variety of machinery, including stationary steam engines, chemical plant and winders for mines, including gold mines. The works closed in 1977.

[10] Ibid., p. 197.

[11] Ibid., p. 201.

[12] Monthly Army List, December 1912, p. 853.

[13] Monthly Army List, April 1914, p. 857.

[14] Monthly Army List, February 1915, p. 678.

[15] Monthly Army List, February 1915, p. 851.

[16] Monthly Army List, April 1915, p. 857.

[17] Sir Archibald Murray’s Despatches (June 1916-June 1917). J.M. Dent & Sons, Ltd., London and Toronto, 1920, p. 181.

[18] Soldiers Died in the Great War.

[19] The nature of his illness is unknown.

[20] Monthly Army List, June 1918, p. 703.

[21] Mildred had previously commanded the 73rd Field Company, R.E.

[22] It is not known whether Major Hordern was wounded during the battle.

[23] Note that the men at this time still had four digit Territorial Force regimental numbers. Their numbers were not changed to the 420XXX series until the company was redesignated as the 406th (Renfrew) Field Company.

[24] Hodgart may have been awarded the Military Cross for his actions during the battle of the Somme, although as indicated in this research work, no official evidence of that award has been located.

[25] The Great War 191418 Community Facebook page.

[26] London Gazette, No. 8811, p. 17.

[27] The 406th (Renfrew) Field Company lost a total of 23 men during the war.

[28] London Gazette, No. 38, p. 18.

[29] The Special Constabulary Long Service Medal is long service medal awarded in the United Kingdom to members of the Special Constabulary who have completed a specified period of service. Established in 1919 by King George V, the medal was initially created to reward members of the Special Constabulary for their service during the Great War of 1914-1918.

[30] Hugh Maclure Hodgart’s name appears on page 364 of Army Honours and Awards as having won the Military Cross. The list containing his name was originally published in the Army List of April 1920. The data from this Army List were reproduced in Army Honours and Awards by J.B. Hayward and Son, London, in 197_. His name also appears on page 2393f of the December 1920 Army List under Renfrewshire Fortress Engineers (Territorial Force Reserve). The entry includes the postnominal M.C. next to his name. His medal group, when purchased by the author, did not include an M.C. A tailor’s specimen was added to his medals to “complete” the group.

[31] Monthly Army List, December 1920, p. 681.

[32] Monthly Army List, December 1920, p. 2393f.

[33] A letter from Hugh’s son Charles Glen Hodgart, written to the author in 1977, indicated that a portrait of Hugh Maclure Hodgart hung in the Board Room of the firm. It may be inferred that H.M. Hodgart was an officer of the firm for his portrait to be put on display in such a manner. C.G. Hodgart also indicated that this was the only picture of his father that he had; that is, he had no photographs of him.

[34] Monthly Army List, June 1926, p. 347a.

[35] Merchiston Castle School Register, p. 324.

[36]

Monthly Army List, October 1935,

p. 40.

[37] Merchiston Castle School Register, p. 201.

[38] Monthly Army List, October 1935, p. 339b.

[39] Merchiston Castle School Register, p. 201.

[40] Ibid.

[41] Ibid., p. 197.

[42] Ibid., p. 339.

[43] Email dated 30 November 2000 from Hugh Hodgart. The date when Charles became a Justice of the Peace apparently was 1960 and not 1938 as stated in the Merchiston Castle School Register, p. 234.

[44] Merchiston Castle School Register, p. 201.

[45] Later, Lieutenant Colonel Eric Wakeling, R.E. Born 1 August 1920. Died 11 November 2013.

[46] Ibid., p. 345.

[47] Ibid., p. 339.

[48] Ibid., p. 324.

[49] The Sapper, November 1956, p. 146.

[50] Email dated 30 November 2000 from Hugh Hodgart.