Lieutenant

Colonel

JOHN ANCRUM CAMERON

Royal Engineers

By

Lieutenant

Colonel Edward De Santis

Ó

2003. All

Rights Reserved.

1. INTRODUCTION

John Ancrum Cameron came from a military family of distinction. His grandfather, Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Cameron, C.B. served with the 42nd Regiment of Foot during the Indian Mutiny and died at Bareilly on the 9th of August 1858. His father, Major Sir Maurice Alexander Cameron, K.C.M.G., R.E. served as Surveyor General of the Straits Settlements and was a Crown Agent for the Colonies. John Cameron had two brothers; Ewen Arthur Cameron and Alexander Cameron, both of whom served in the Army. Lieutenant Ewen Arthur Cameron served with the Royal Field Artillery and was killed during the Great War of 1914-1918. Alexander Cameron, K.B.E., C.B., M.C. served in the Royal Engineers and rose to the rank of Lieutenant General. Although this research is primarily about John Ancrum Cameron much information also is presented about the men previously mentioned. Their stories will be told at the end of this narrative.

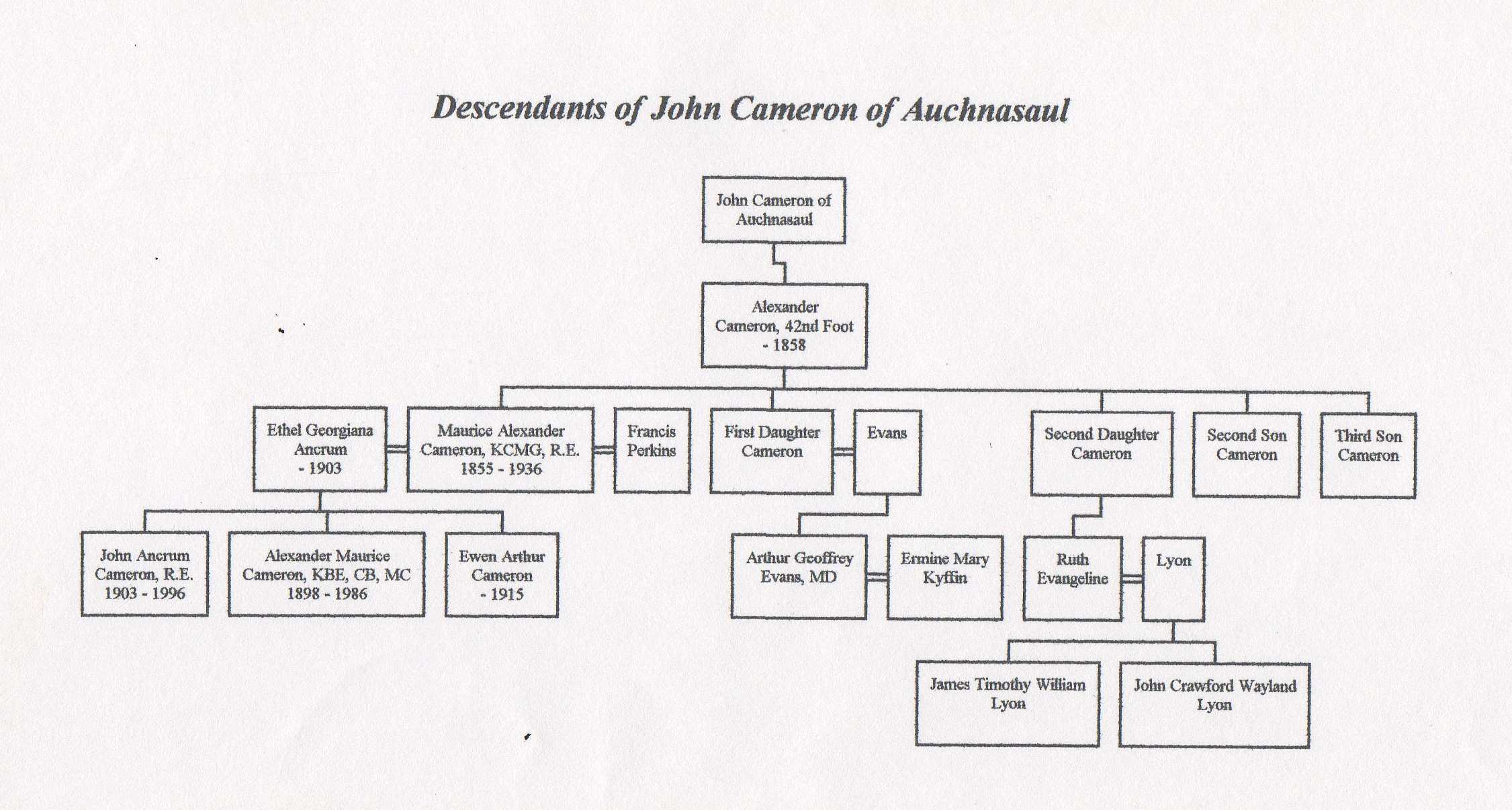

Figure 1. The Cameron Family Tree.

2. EARLY LIFE AND FAMILY INFORMATION

John Ancrum Cameron was born on the 27th of August 1903 at 27 Brunswick Gardens, Kensington, in the County of London [1]. His father was Major Sir Maurice Alexander Cameron, K.C.M.G., an Old Wellingtonian, and his mother was Ethel Georgiana Cameron, daughter of William Rutherford Ancrum of Upton St. Leonard’s Court, Gloucester [2]. John was baptized in the Parish of Upton St. Leonards on the 27th of September 1903.

Figure 2. The Cameron Family

Home at 27 Brunswick Gardens, Kensington

(Photograph

courtesy of Google Earth)

John never got to know his mother, as she died in September of 1903, only three weeks after his birth, possibly from complications during childbirth [3]. In 1911 at age 7 young John was at Camberley, Surrey as a visitor in the household of Captain Lambert Cameron Jackson, Royal Engineers. The census return for that year shows the following information:

Census Place: Camberley, Surrey |

|||||

Name and Occupation |

Relation |

Marital Status |

Age |

Sex |

Birthplace |

Lambert Cameron Jackson, Captain, Royal Engineer |

Head |

Married |

35 |

Male |

County Galway, Ireland |

Olive Margaret Jackson |

Wife |

Married |

28 |

Female |

Farnborough, Hampshire |

Maurice Alexander Cameron, Retired Major, R.E. |

Uncle |

Widower |

55 |

Male |

Stirlingshire, Scotland |

John Ancrum Cameron, |

Cousin |

|

7 |

Male |

Kensington, |

Laura Puill |

Servant |

Single |

28 |

Female |

Farnham, |

Lilian Rose Alexander |

Servant |

Single |

21 |

Female |

Finley, |

In all probability he was raised by a nanny with the help of other family members and at the age of 13 he entered Wellington College at the start of the Michaelmas Term [4]. While at Wellington he lived in Anglesey Dormitory House and became Dormitory Prefect and Head of Dormitory. He also played for the school VI. While at Wellington College he spent many happy days between terms visiting with his grandmother at Upton St. Leonards and with his Aunt Alice, visits that began in 1918 [5].

Figure 3. John Ancrum Cameron at

Age 12.

(Photograph courtesy of John Lyons)

In 1922 John left Wellington College after the Lent Term. He passed out very well with his family teasingly saying that it was "on account of his good handwriting." [6] Obviously this was not the whole story, as John was accepted at the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich, a distinction that would not have been granted to him solely on the merits of his handwriting. John did well at Woolwich and on the 26th of August 1924 he was commissioned a Second Lieutenant in the Corps of Royal Engineers [7].

3. TRAINING

Following his commissioning in the Royal Engineers, 2nd Lieutenant Cameron reported to the School of Military Engineering at Brompton Barracks, Chatham, Kent for further training as an engineer officer. He spent two years at Chatham and on the 26th of August 1926 he was promoted to the rank of Lieutenant at about the same time that he received orders assigning him to the Queen Victoria’s Own Madras Sappers and Miners in India [8]. This assignment to a unit of the Indian Army was to be a significant milestone in his life, as he spent most of his career with the Indian Sappers and Miners and came to love India and the Indian people.

Figure 4. John Ancrum Cameron and

his New Roadster, c. 1925.

(Photograph courtesy of John

Lyons)

The photograph above shows Cameron driving his new automobile with friends in the "dickey seat" and a petrol can on the running board. He was a man who kept up with the times. Even before World War 2 he traveled home to England on leave from India by air, while most still traveled by sea.

4. ASSIGNMENTS AND CAMPAIGN SERVICE

Bangalore, India (1927)

Lieutenant Cameron arrived in India in 1927 and was assigned initially as the Assistant Adjutant of the Madras Sappers and Miners at St. John’s Hill in Bangalore. Anxious to get an assignment with the troops in the field, Cameron remained at Headquarters for only a short time before being assigned to the 10th Field Company, Madras Sappers and Miners at Razmak on the North West Frontier in 1928 [9]. It here that he would have his first experience with active service in the field as a company officer. See Map 1, Addendum No. 4.

North West Frontier (1929-1931)

In April of 1930 a rebel organization known as the Redshirts, under Abdul Ghaffar, began causing trouble along the Mohmand Frontier and in the border villages. The British found it necessary to establish a blockade line and an improved road system to ward off these rebels. A few minor actions were fought, but most of the period through March of 1931 was spent in making roads and building posts. A small expedition also was sent into Tirah during this period.

Lieutenant Cameron saw his first action on the 11th of May 1930 when 4,000 Tochi Wazirs attacked Datta Khel and were driven off by the Razmak Column, which included the 10th Company, Madras Sappers and Miners. Although the attack by the tribesmen was beaten off, the Circular Road between Razmak and Jandola was closed for some time. On the 10th of July 1930 Cameron’s company along with the Razmak Column advanced to Tauda China and afterwards through Dwa Toi to Ladha. This advance ended the hostilities in Waziristan [10]. For his participation in the campaign, Lieutenant Cameron was awarded the India General Service Medal 1908-1935 with clasp [NORTH WEST FRONTIER 1930-31] [11]. See Map 2, Addendum No. 4.

Figure 5. Lieutenant John Ancrum

Cameron, Christmas Day, 1930, in the Khyber Pass

(Photograph

courtesy of John Lyons)

Bangalore, Home Leave and Dacca (1931-1934)

In March of 1931 Lieutenant Cameron was still serving as a company officer with the 10th Company, Madras Sappers and Miners. By this time the company had returned to Bangalore [12].

Figure 6. Lieutenant Cameron and

the 10th Company, Madras Sappers and Miners Field Hockey Team, c.

1931.

(Photograph courtesy of John Lyons)

In December of 1931 Cameron went on home leave to England [13]. He remained on leave for 8 months and returned to India on the 18th of August 1932 when he again took up his position as a company officer with the 10th Company, Madras Sappers and Miners at Bangalore [14,15]. He served with the 10th Company until December of 1932 when he again took the post of Assistant Adjutant of the Corps at Bangalore [16]. This posting was a short one, however, for in March of 1933 he was assigned as a Company Commander of the Training Battalion, Madras Sappers and Miners at Bangalore [17].

Lieutenant Cameron served with the Training Battalion until April of 1934 when he was again assigned to a field unit. This time he was posted as a company officer to No. 11 Army Troops Company, Madras Sappers and Miners at Dacca [18]. He remained with this company for only a short time and in July of 1934 he left the Madras Sappers and Miners for other duties with the Military Engineer Service. See Map 3, Addendum No. 4.

Figure 7. Lieutenant Cameron and

his Section of Madras Sappers and Miners.

(Photograph

courtesy of John Lyons)

This photograph of Cameron was probably taken between 1931 and 1935. Cameron and the Corporal on his left are both wearing the ribbon bar of the India General Service Medal 1908. He is wearing two pips of a Lieutenant in the photograph and as he was promoted to Captain in 1935, this dates the photograph within the period cited.

Fort Sandeman (1934-1935)

Cameron was assigned to duties with the Military Engineer Service, Zhob and Sind [19]. After reporting to the M.E.S. he was assigned as the Assistant Garrison Engineer at Fort Sandeman [20]. He served in this capacity until 1936 when he was reassigned, after his promotion to Captain, as Officer Commanding, No. 11 Army Troops Company, Madras Sappers and Miners in Bangalore. In 1938, after about two years with his old company, he was posted as Officer Commanding the 15th Field Company, Madras Sappers and Miners the 12th Indian Infantry Brigade in Singapore.

Figure 8. Fort Sandeman in

Zhob.

(Photograph courtesy of History of Pashtuns)

Preparations for War (1939-1942)

Following his appointment to Acting Major in September 1939, Cameron returned to Bangalore and assumed new duties as the Officer Commanding the 14th Field Company, Madras Sappers and Miners. By this time his experience with the Indian Army in general and the Madras Sappers and Miners in particular was great indeed. During the 12-year period between 1927 and 1939 he had served as Adjutant of the Corps and as a company officer or Officer Commanding a training company, three field companies and an army troops company, as well as performing duties as a Garrison Engineer. An officer who served under Cameron in the 14th Field Company had this to say about him [21]:

"I owe him much for he taught me the ins and outs of the Indian Army and in particular how to defeat the babu machinery. He was eccentric but kind even though when roused his temper was explosive. In those days he was a bachelor, teetotal and a regular church-goer, but he was certainly not dry in other respects. I enjoyed being under his command and I know that the Tamil and Telegu VCOs [22] and Ors [23] worshipped him."[24]

In April of 1941 Major Cameron assumed command of the 15th Field Company, Madras Sappers and Miners. He remained in this position only until November of 1941 when he relinquished command in preparation for his assignment to another unit. That assignment came in February of 1942 when he was posted as Officer Commanding the 12th Field Company, Madras Sappers and Miners with the 4th Indian Division. This assignment would take him into the heat of battle against the Axis forces in World War 2.

North Africa (1942 - 1943)

Cameron arrived at his new company just in time to get caught up in Field Marshal Rommel’s counter offensive against the British Eighth Army. The Eighth Army had hardly occupied Benghazi when it was ordered to demolish its port facilities and to withdraw. The 12th Field Company and the other 4th Indian Division Engineers carried out extensive demolitions in Benghazi and then withdrew eastwards towards the Gazala line. A lull in operations occurred at this time and the 4th Division Engineers helped the infantry to lay mines and prepare anti-tank defences. Half a million mines were laid.

During this period and in fact during most of the North African campaign, the 12th Field Company directly supported the 7th Infantry Brigade of the 4th Indian Division.

On the 27th of May 1942 Rommel aimed a powerful attack at Gazala and by the 10th of June the Germans had breached the British defensive line. The British Eighth Army carried out a withdrawal to the Egyptian border, leaving behind only the garrison at Tobruk. The 4th Indian Division was relieved by the 5th Indian Division and the brigades of the 4th Division, in infantry brigade groups, were sent separately to Cyprus, Palestine and the Suez Canal Zone. Cameron and his company, in support of the 7th Infantry Brigade Group, went to Cyprus. See Map 4, Addendum No. 4.

This dispersal of his men to all points of the compass was a bitter blow to the Divisional Commander, Major General F.I.S. Tuker, CB, DSO, OBE. Ever since assuming command of the division his mind had been engrossed with the problems of desert warfare. Now his division had been committed piecemeal to defensive operations in widely dispersed areas. General Tuker expressed his bitterness as follows in a letter to the Deputy Commander-in-Chief, India:

"I have always opposed the pernicious infantry brigade group system. It does for small wars but it is rubbish for modern warfare. It leads to confusion, dispersion, unbalancing of forces and chaotic planning."[25]

Figure 9. Major General Francis Ivan Simms Tuker, CB, DSO, OBE.

Division Commander, 4th Indian Division

(Photograph courtesy of Wikipedia)

As a man of action, John Cameron was not thrilled either with the idea of his company taking a back seat on Cyprus while the big show was ongoing in North Africa.

The mission of the 7th Infantry Brigade Group on Cyprus was one of defence of the island and its military facilities. The previous scheme of defence for Cyprus had scattered the defenders in small groups covering the ports and beaches. In such dispersal the garrison represented little more than a liability to the Royal Navy. General Tuker proposed to concentrate his forces in a central position to provide the colony with the capability to withstand siege. The 7th Infantry Brigade took part in anti-invasion exercises and indulged in an extended period of training on the Cypriot mountainsides. Although not known at the time, these maneuvers would be valuable training for the upcoming operations in the mountains of Italy. Training for the 12th Field Company, however, was not as realistic as it could have been and sorely disappointed John Cameron. The engineer tasks for the anti-invasion exercises were chosen by infantry officers without engineer advice [26]. Engineer training consisted of road craters, railway bridge demolitions, mined chambers in rock and similar jobs, all of which could be accomplished in an hour or two by the planting of notice boards. No actual work was carried out and the Sappers gained very little experience from these simulated activities. Cameron was justifiably frustrated by this lack of realistic training for his officers, non-commissioned officers and men.

During the spring and early summer of 1942, many changes were made in commands throughout the division. Of particular interest to Major Cameron was the assignment of Lieutenant Colonel John H. Blundell, OBE, R.E. as his new boss, replacing Lieutenant Colonel H.P. Cavendish, DSO, OBE, R.E. as the CRE of the division.

In the third week of August 1942, the 7th Brigade along with its supporting units were relieved in Cyprus and moved to Egypt. The 4th Indian Division reassembled and rejoined the British Eighth Army in November of 1942 prior to the pursuit of Rommel’s forces after the Battle of Alam el Halfa. At last Cameron and his men were back in the action in North Africa.

On the 4th of November 1942 the 12th Field Company was assigned to a flying column whose mission was to round up prisoners, guns and equipment left behind by the retreating Italians in Rommel’s force. Cameron and his company took part in this operation for several days, primarily with the mission of clearing minefields. On the 7th of November 1942 the 4th Indian Division was withdrawn from offensive operations and Major Cameron’s company and the rest of the 4th Division Engineers were left behind at El Alamein on salvage operations to clear the battlefield. They rejoined the Eighth Army for its final attack on the Mareth Line [27]. See Map 5, Addendum No. 4.

The British attack on the Mareth Line commenced on the 20th of March 1943 with the 50th Division of British XXX Corps leading the attack. Casualties in the attack were extremely heavy and rains badly damaged a causeway across Wadi Zig-Zaou constructed by the 50th Division Engineers, thus hindering the forward movement of heavier tanks to support the infantry assault. On the night of the 21st/22nd of March 1943, heavy rain brought the wadi down and further damaged the crossing. On the 22nd of March, the Sappers and Miners of the 4th Indian Division were placed under orders of the 50th Division. During the afternoon of the 22nd the enemy counterattacked strongly and considerably reduced the bridgehead across the Wadi Zig-Zaou. When the engineers started work that evening to build two new causeways, conditions were extremely difficult. Led by their C.R.E., Lieutenant Colonel J.H. Blundell, R.E., and the two company commanders, 4th and 12th Field Companies plunged into the wadi bed and worked feverishly with fascines and wire mesh to build the causeways.

The enemy was on the offensive and at very close range. The wadi was an inferno of fire. The rising moon silhouetted the men working on the east bank and transport blocked the approaches to the crossing sites. When enemy fire opened up on the sapper parties, British covering detachments replied. From front and rear over the heads of the sappers, tracer rounds, mortars and sheets of machinegun fire streamed. Then the field guns joined in. Between the walls of exploding shells the engineers grappled with their task. The area around the Wadi Zig-Zaou was transformed into a block of dust and fumes, shot with flames rising into the luminous sky [28].

On the approaches to the wadi, vehicles continued to unload infantry for the coming assault. The press of transport blocked the sapper lorries carrying the steel mesh for the causeway. In the wadi itself in the midst of an ear-splitting din and a hail of bullets, the work proceeded calmly and steadily. Madrassi and Sikh Sappers and Miners lived up to the cool and imperturbable behaviour of their officers. Major W.J.A. Murray and Lieutenant J.R.S. Baldwin of the 4th Field Company and Major John A. Cameron and Subedar Sampangiraj of the 12th Field Company supervised the tasks as calmly as though on exercises [29].

Lieutenant Colonel Blundell was everywhere encouraging his men with his cheery laugh and exhortations. He pointed out how safe others must be since a man of his height remained unhit (although he actually had the peak of his cap shot off). In the middle of the bridging operations an infantry officer reached the wadi to ask for mine detectors in order to clear a way to one of his men who had been blown up in a minefield. Without hesitation Lieutenant Colonel Blundell and a sapper proceeded to the rescue. When the sapper was hit by machinegun fire, Blundell sheltered him with his body and carried him to safety.

Hour by hour the work continued. Small groups of men dashed forward a few yards at a time to deliver material to the workers in the cleft of the wadi. The ramps were cut, the fascines laid and the ballast spread to make firm crossings. At 3:30 a.m. on the morning of the 23rd of March 1943 the enemy put down a heavy barrage in preparation for a further counterattack. Under the fire the causeways were finished and Blundell, Cameron and their men withdrew started to withdraw from the wadi.

The Sappers and Miners might have been pardoned had they scurried for safety. But along the wadi the assault infantry waited. Before withdrawing Blundell explained to his men that it might have an unfortunate effect upon these troops if men were seen running to the rear. He therefore ordered that all should move back at a casual pace, chatting and joking as if on some ordinary occasion. Blundell himself left the area last, walking even more slowly than the others and stopping to talk to infantry groups to explain the situation while his men waited for him. On such occasions the Sappers and Miners halted around their officer, moving only when he moved. This cool behaviour was not wasted or frivolous. Many units bore witness to the heartening effect of the coolness, confidence and bearing of the Indian Sappers and Miners at Wadi Zig-Zaou [30]. The coolness and bravery of Major Cameron and the other officers and men of the 4th and 12th Field Companies during this action were truly extraordinary. It is difficult to understand why Cameron did not deserve the Military Cross or a least a mention in despatches for his brave conduct at Wadi Zig-Zaou.

The 4th Indian Division fought its way towards Tunis through the Matmata Mountains near Mareth and Zarat from the 25th through the 28th of March 19143. Major Cameron’s next action with the 12th Field Company, Madras Sappers and Miners came on the 6th of April 1943 during the attack at Wadi Akarit. The attack on the Axis position was launched by British XXX Corps with the 51st Division on the right, 50th Division in the centre and the 4th Indian Division on the left. The divisional engineers of all three divisions had the task of making gaps in the minefields covering the position and making crossings over anti-tank obstacles. This they did under heavy fire. All three field companies had come forward to work on a track that would carry the divisional vehicles across the Oudane el Hachana ridges and the work went forward in the customary imperturbable fashion of the Indian Sappers and Miners. See Map 6, Addendum No. 4.

During the course of the work a German artillery salvo took a tragic toll. At 1600 hours when Lieutenant Colonel John Blundell was conferring with his officers, a shell struck in the midst of the group of officers. Major W.J.A. Murray, MC, R.E., commanding the 4th Field Company and Captain Baldwin were killed outright, together with Lieutenant Allan, an American liaison officer who had joined the 4th Indian Division Engineers in Cyprus. The courageous Lieutenant Colonel J.H. Blundell was so seriously wounded that he died in the dressing station. See Addendum No. 5.

Figure 10.

Officers of the 4th Indian Division Sappers and Miners Killed at

the Battle of Wadi Akarit.

(Photograph courtesy of STEVENS,

G.R. Fourth Indian Division. McLaren and Son Limited, Toronto,

1948).

General Tuker wrote the following regarding Blundell:

"He died yesterday evening, mourned by thousands of humble Indian soldiers."

The Commandant of the Bengal Sappers and Miners on hearing of Blundell’s death remarked:

"He is the greatest individual loss that this Corps has so far suffered."[31]

After the death of Lieutenant Colonel Blundell, Major Cameron relinquished command of this company, was appointed an Acting Lieutenant Colonel, and assumed the duties of the Commander Royal Engineers for the division [32]. Although honoured by this promotion, Cameron was very much saddened by the death of his old boss who he held in very high esteem.

Lieutenant Colonel Cameron took part in the final assault on the Axis forces in North Africa and the capture of Tunis. This took the 4th Indian Division Engineers through Sfax, El Djem, Sousse, Enfidaville and into action at Djebal Garci on 19-20 April 1943. On the 6th of May 1943 the British IX Corps, with 4th British and 4th Indian Divisions making the main attack at Medjaz el Bab, opened up the attack to penetrated the German position, with the British 6th and 7th Armoured Division tasked to exploit the penetration. The armoured divisions were to move through the gap opened by the infantry and secure the high ground immediately west of Tunis, thus breaching the inner defences of the town. The chief job of the engineers in preparation for the attack was to prepare routes forward for the armour. This included clearing gaps through enemy minefields as far forward as possible. Major Cameron’s 12th Field Company, assisted by 200 Gurkha soldiers, also rebuilt 80 feet of roadway that had been cratered by the enemy to the north of Ste. Marie du Zit.

The overall British attack went entirely according to plan and victory was complete. The Germans surrendered on the 12th of May 1943 and Lieutenant Colonel Cameron’s sappers were then put to work on clearing minefields and booby traps, bridging work, establishing water points and constructing prisoner of war cages. On the 17th of May 1943 the 4th Indian Division began to trek back to Tripolitania and a week later the division concentrated at Misurata, on the sea coast 120 miles east of Tripoli. Here the men of the Indian Sappers and Miners, along with the rest of the division, got a well earned two week’s rest.

Light training began early in June; however, on the 13th of June 1943 word was received that His Majesty the King-Emperor was in Africa and would review the 4th Indian Division on the 19th of June. While still serving as the Commander Royal Engineers of the 4th Indian Division, Lieutenant Colonel Cameron was chosen to command the Victory Parade in North Africa during a visit of H.M. King George VI. This honour was bestowed on him because of his superb command of the Indian languages. His competence with the languages was in fact so great that he was called upon to interpret for the King Emperor during the parade [33]. This competence with the language was developed by Cameron as a direct result of his esteem for his Indian soldiers and his desire to learn their customs and to be able to communicate fluently with them. He demonstrated this keenness to learn their languages early in his career and continued it for most of his life.

Cameron’s organization of the Indian Sappers and Miners for the review by the King-Emperor was meticulous. The troops rehearsed their part in the review until their performance was near perfection. On the grand day the parade was formed at 1400 hours and Cameron held one final practice before the troops were stood easy. At 1450 hours cheers could be heard in the south as the King’s car passed the divisional headquarters. The Indian Sappers and Miners were honoured to be on the right of the line, immediately after the Royal Artillery. This made them the first Indian unit to be inspected by the King-Emperor.

The cheers drew closer as the King passed the each field regiment of artillery. At the appropriate moment Cameron gave the order: "The Sappers will come to attention!" followed by the orders of each of the officers commanding the companies to bring their units to attention. The Royal car passed the 12th Field Company and then the 11th Field Park Company and stopped opposite Lieutenant Colonel Cameron who was presented to the King by General Tuker. In addition to General Tuker, Field Marshall Montgomery also was in the Royal car.

Cameron shook hands with King George VI and presented one of his VCO’s, Subedar Narinder Singh, to His Majesty. The King, looking pleased with the Sapper and Miners, pronounced them "A good lot" at which time Cameron took a pace to the rear and ordered, "Sappers and Miners, three cheers for His Majesty the King-Emperor." As the Sappers cheered, the officers raised their caps and the men their right hands in salute. In the evening General Tuker returned to visit with the 4th Division Sappers and Miners. Lieutenant Colonel Cameron gave his men each a bottle of beer with which to drink the health of the King-Emperor. The Pathans of the unit drank tea instead [34].

For his work during the capture of Tunis, Lieutenant Colonel Cameron is mentioned in the history of the 4th Indian Division with these words [35];

"Lieutenant Colonel JA Cameron, CRE, an efficient Scotsman, led the Sappers and Miners in the magnificent tradition of their Corps."

For his services in North Africa, Lieutenant Colonel Cameron was awarded the Africa Star [36]. As mentioned previously, he did not receive a decoration or even a mention in despatches although his command of the 12th Field Company under fire was exemplary. One wonders if such an award would have been forthcoming if Lieutenant Colonel Blundell had not been killed. His death prior to the end of the campaign in North Africa may have denied Cameron a much deserved award.

Italy (1943 – 1944)

The 4th Indian Division played an extensive role in the campaign in Italy where it served in the actions leading to two bloody assaults on the German positions at Monte Cassino. During these operations the engineers constructed and repaired mountain roads, installed barbed wire barriers and placed minefields in support of the attacking infantry. See Map 7, Addendum No. 4.

Following the capture of Monte Cassino the division undertook operations on the lower Adriatic and in Central Italy. It also participated in Operation Vandal and in operations against the Gothic Line during August and September of 1944. At the end of September 1944 the division assembled in the vicinity of Lake Trasimeno to reorganize, refit and train for upcoming operations. Instead, the division received word that it would leave Italy and proceed to Greece. See Maps 8 and 10, Addendum No. 4.

Lieutenant Colonel Cameron performed his duties as the division’s C.R.E. during the entire campaign in Italy and was awarded the Italy Star for his services [37]. It is believed that he continued these duties with the division after its move to Greece [38]. See Map 9, Addendum No. 4.

The 4th Indian Division sailed from the port of Taranto in November of 1944 and its transports rendezvoused at the island of Skiathos in the northern Aegean, where an advanced base had been established. The division engineers immediately began a survey of the docks and went to work on the roads. Lieutenant Colonel Cameron appears to have remained as the Commander of the 4th Indian Division Engineers until late January or early February of 1945 when he returned to India.

India (1945 – 1948)

On the 9th of February 1945, sometime after his return to India from Greece, Lieutenant Colonel Cameron was appointed Assistant Commandant (Administration) of the Madras Sappers and Miners at Bangalore. On the 23rd of May 1946, while at Bangalore, Cameron was mentioned in despatches for his outstanding service in the Mediterranean Theatre [39]. In addition he was awarded the 1939-45 Star, the Defence Medal and the War Medal for his services during World War 2 [40].

Malaya (1948 – 1970)

In June of 1948 field operations were begun against the Communist insurgents in Malaya. Lieutenant Colonel Cameron was ordered to Malaya where, on the 30th of May 1949 he was appointed Assistant Director of Works. He served with distinction in this capacity and on the 27th of April 1951 he was mentioned in despatches for his services in Malaya [41]. He was also awarded the General Service Medal with clasp [MALAYA] [42].

It appears that John Cameron liked his time in Malaya and decided to stay on even after he retired from the Army in July of 1952. Counterinsurgency operations were still on going at the time and in fact continued until July of 1960. After leaving the Army, Cameron found employment as a Security Officer in Pahang, Malaya. The precise nature of this work is not known, although one would suspect that it involved training of local security forces. Additionally, between 1953 and 1957 he served as the Commanding Officer of the Pahang and Selangor Home Guard and was involved in combating Communist guerrillas. He apparently had some very unpleasant experiences while in Malaya that he mentioned to members of his family at home, but was unwilling to talk about in detail [43].

He took a considerable interest in the people while serving in Malaya, just as he did with his Indian soldiers. He got involved with a church group of Christian Malays and he was injured in a serious motor accident while taking a group of local people to church for a Good Friday service [44].

Except for a trip to England in 1953 to celebrate his 50th birthday with relatives at the Falcon Hotel in Bromyard, John Cameron remained in Malaya until 1966 when it appears that he returned to England to stay [45]. In 1970 he was still using Lloyds Bank Ltd. in London as his mailing address [46].

5. PROMOTIONS

John Ancrum Cameron received the following promotions during his time in service:

Date of Promotion or Appointment |

Rank or Position |

26 August 1924 |

2nd Lieutenant (a) |

26 August 1926 |

Lieutenant |

26 August 1935 |

Captain [47] |

September 1939 |

Acting Major |

26 August 1941 |

Major [48] (b) |

4 April 1943 |

Acting Lieutenant Colonel |

1949 |

Lieutenant Colonel (c) |

NOTES:

a. Appointment as a 2nd Lieutenant in the Corps of Royal Engineers: The London Gazette, 26 August, 1924, p. 6422.

b. Promotion to Major: Supplement to The London Gazette, 26 August , 1941, p. 4936.

c. Promotion to Lieutenant Colonel: Supplement to The London Gazette of Tuesday, 6th September, 1949. Friday, 9 September , 1949, page 4333.

6. SUMMARY OF MILITARY SERVICE

Location |

Period of Service |

Chatham, Kent |

June 1924 – August 1926 |

Bangalore, India |

August 1926 – December 1929 |

Razmak, North West Frontier, India |

December 1929 – March 1931 |

Bangalore, India |

March 1931 – April 1934 |

Dacca, India |

April 1934 – July 1934 |

Fort Sandeman, India |

July 1934 – 1936 |

Bangalore, India |

1936 – February 1942 |

North Africa |

February 1942 – November 1943 |

Italy |

September 1943 – November 1944 |

Greece |

November 1944 – February 1945 |

Bangalore, India |

February 1945 – May 1949 |

Malaya |

May 1949 – July 1952 |

Location |

Period of Service |

Home Service |

2 years and 2 months |

Service Abroad |

24 years and 11 months |

Total Service |

27 years and 1 month |

As the tables above indicate, Cameron spent almost 25 years of his 27 years, or over 90 percent of his career, in service abroad. All of this service abroad was with the Indian Sappers and Miners. As a bachelor, he had no ties of wife and children to prompt him to return to England. He loved India and was content to serve there.

7. EDUCATION AND QUALIFICATIONS

a. Education: John Ancrum Cameron’s educational qualifications are as indicated in the table below:

Date |

Educational Qualification |

Lent Term, 1922 |

Graduated Wellington College |

26 August 1924 |

Graduated Royal Military College at Woolwich |

He may have attended various military courses during his career; however, direct access to this service papers prevented a determination of this information.

b. Positions and Qualifications: John Ancrum Cameron served in the following positions and earned the following qualifications during his time in service.

Date |

Position or Qualification |

1927 |

Assistant Adjutant, Madras Sappers and Miners |

1928 |

Field Company Officer, Madras Sappers and Miners |

December 1929 |

Member, Institution of Royal Engineers [49] |

March 1933 |

Training Company Commander, Madras Sappers and Miners |

April 1934 |

Army Troops Company Officer, Madras Sappers and Miners |

July 1934 |

Assistant Garrison Engineer, Military Engineer Service |

1936 |

Army Troops Company Commander, |

1938 |

Field Company Commander, Madras Sappers and Miners |

6 April 1943 |

Commander Royal Engineers |

9 February 1945 |

Assistant Commandant (Administration), |

1 September 1948 |

Staff Officer Royal Engineers 2 |

30 May 1949 |

Assistant Director of Works |

1952 |

Security Officer, Pahang, Malaya |

1953 |

Commanding Officer, Pahang and Selangor Home Guard |

Again, it should be noted that the vagueness of some of the dates is due to the lack of access to his military service record from the Ministry of Defence. NOTE: Based on the current Ministry of Defence rules in the U.K., Cameron's service records will not become available to the public until 2021; that is, 25 years from his date of death.

8. MEDALS, DECORATIONS AND AWARDS

Lieutenant Colonel John Ancrum Cameron was awarded the following medals and decorations during his time in the Army:

Figure 11. The Cameron Medals in

the Author's Collection.

(Photograph from the author’s

collection)

The medals are, from left to right, the India General Service Medal 1908 with clasp [NORTH WEST FRONTIER 1930-31], the 1939-45 Star, the Africa Star, the Italy Star, the Defence Medal, the War Medal with Mention in Despatches oak leaf and the General Service Medal with clasp [MALAYA]. The Indian General Service Medal 1908 is not Cameron's actual medal. At sometime during his life he lost his original medal. This medal is actually named to 14988 SPR. KAKA KHAN. BENGAL S. & M. It has been added to Cameron's group of medals solely as a specimen replacement. The General Service Medal is named to LT.COL. J.A. CAMERON. R.E. The remainder of the medals are un-named, as issued. The Supplement to the London Gazette dated 27 April 1951, page 2384, indicates that 30513 Lt. Col. J.A. Cameron, Corps of Royal Engineers was mentioned in despatches for his service in Malaya. The citation for the Mention in Despatches reads:-

The War Office, 27th April, 1951

The King has been graciously pleased to

approve

that the following be Mentioned, in recognition

of

gallant and distinguished services in Malaya, during

the

period 1st July to 31st December, 1950: -

CORPS OF ROYAL ENGINEERS

Lt.-Col. J.A.

Cameron (30513)

9. POST SERVICE LIFE

The Supplement to The London Gazette dated the 1st of July 1952 lists Lieutenant John Ancrum Cameron as retired from the Army on retired pay effective the 4th of July 1952. The Second Supplement to The London Gazette of the 29th of April 1952 (dated 2 May 1952) had previously listed him as completing his tenure as a Regimental Lieutenant Colonel remaining on full pay (supernumerary) with an effective date of the 12th of April 1952. He apparently remained with the Reserve of Officers until the 24th of December 1958 when the Supplement to The London Gazette of 23 December 1958 shows him as having exceeded the age limit and ceasing to belong to the Reserve of Officers.

John Ancrum Cameron resided at 24 Broad Street, Bromyard, Herefordshire HR7 4BS from 1983 to 1996 [50]. According to a family member, he chose Bromyard as his retirement home because of the many happy memories he had of his school holidays spent in the area with relatives.

On the 3rd of June 1986 he had his Last Will and Testament prepared by Lloyds Bank. Although he was never married, he had numerous friends and relatives to whom he was very generous in his will. Among these were three godsons and four goddaughters [51].

Also mentioned in his will was The Lower Sapey Centenary Fund, a trust for Saint Bartholomew’s Church in Lower Sapey Parish, Clifton-on-Teme, Worcestershire, where John Cameron attended and worshipped. Old Saint Bartholomew’s church at Lower Sapey is an historic building and a rare example of an almost unchanged rustic Norman church modified from time to time over the centuries. There even is mention of a priest from the church in the Domesday Book. Evidence of an even earlier church on the site has discovered at the site.

St. Bartholomew’s Church is located in beautiful and remote countryside, perched on a steep bank above a stream and reached by a long winding lane. A 17th century timber-framed farmhouse is its only neighbour. The charm and interest of St Bartholomew’s lie in the fact that little has changed since it was built in Norman times. It is very simple in form. The oak porch, weathered to a beautiful silvery-grey, leads to a splendid door set within a fine Norman doorway. Inside the church is simplicity itself – plain plastered walls and ceilings, a floor made of clay and gravel, and a little west gallery. Wall paintings are faintly visible on the north wall of the church, with fragments dating from the Middle Ages. Most of the fittings were transferred when a new and more convenient parish church was built in Victorian times. St Bartholomew’s was neglected for more than a century after this, and was even used as a farm building. Only in the last 20 years, thanks to efforts of local people, has it been rescued from oblivion. Undoubtedly this rescue was assisted in part by John Ancrum Cameron.

The fact that John Ancrum loved this church is evident from the provision left in his will. Although Cameron served abroad most of his career, he states in his will that the money is being left to the church fund "to mark my happy worship in Lower Sapey for over sixty years." He obviously felt a great attachment to the church and to the community even while he was not in England.

John Ancrum Cameron died on the 26th of August 1996 at the age of 92 at General Hospital in Hereford [52]. He was only one hour and 40 minutes shy of his 93rd birthday when he died [53]. His residence at the time of this death was listed as 22 Buttsfield House, New Road, Bromyard, Herefordshire. This appears to be a nursing home associated with Bromyard Hospital. His cousin, Mr. John Crawford Wayland Lyon of Bockleton Forge, Bockleton, Tenbury Well, Worcestershire was the informant of his death. Cameron’s death certificate lists the cause of death as:

I(a). Pulmonary Embolism and

I(b). Deep Vein Thrombosis.

II. Diabetes Mellitus, Coronary Artery Atheroma and Osteoporatic Fractured Neck of Femur (treated).

His death was certified by Hugh G.M. Bricknell, Deputy Coroner for the County of Hereford and Worcester (Western District) after a post mortem without inquest [54].

John Cameron’s death was registered in the District of Hereford, Sub-District of Hereford, County of Hereford and Worcester on the 13th of August 1996 by J. Davies, Registrar. His will was probated on the 19th of November 1996 with his executor being Lloyds Bank PLC Regional Estates and Tax Office, Broadwalk House, Southernay, West Exeter. John Cameron apparently was a frugal man who, as a bachelor all his life, saved much of his military pay and led a simple life. At his death his estate was values at £272,918 gross, or a net amount of £270,259 after taxes [55].

10. PERSONAL INFORMATION

John Ancrum Cameron, the man, is probably best described in a tribute presented by his Godson Francis Henry Briggs at Cameron’s funeral on the 3rd of September 1996.

"John Ancrum Cameron, also affectionately known as ‘the Colonel’ or ‘Cousin John’ to many of us here, was someone very special and quite unique; which is why we are here not just to mourn a much loved relative and friend, but also to celebrate his life and the pleasure and help he gave others during it.

As a Godson, I know how fortunate I was to have him as my Godfather, and many others have cause to be grateful for his life and the qualities which made him the man we knew and loved; - his intelligence; and his belief in helping with the education of the young; his care and consideration of others; his marvelous, if sometimes rather mischievous sense of humour; his modesty and also his generosity; I think shine all the more in the light of some of his experiences.

Born in Kensington, the youngest of three boys, his mother died when he was three weeks old. There is no doubt (from the stories he told and what was the norm for his generation) that his upbringing was strict; and with the loss of his mother it also probably lacked something of the feminine touch.

However, we do know that some of his happiest early memories were visiting his Grandmother at Upton St. Leonards and visits to his Aunt Alice at Harpley during his school holidays. The earliest recorded visit in the Harpley’s visitor’s book was in Spring of 1918 when he visited from Wellington College.

We know he won many prizes at Wellington and it was from there that he passed into the Elite Army Training Establishment at Woolwich, known as ‘The Shop." History relates that he passed out very well, although his family at the time teasingly said that this was ‘on account of his good handwriting." From Woolwich he joined the Madras Sappers & Miners, but with typical modesty and humour many of his stories of this time related to amusing things or were of practical jokes he had played on his brother officers. But he served the British Empire with loyalty and distinction both in India and North Africa, until the British withdrew from India – a country he loved and whose people he helped – many going on to successful careers.

After India, he went to Malaya as a security officer. Not patrolling factories or warehouses (as we think of security officers today), but repelling guerrillas. If he had unpleasant experiences, he was not forthcoming about them. We do know that he did suffer a serious motor accident at this time whilst taking a group of Malays to church for a Good Friday service.

On returning to Britain, it was understandable that he settled in Bromyard – from his happy memories of school holidays mentioned earlier, his relations in the area, and he had also celebrated his 50th birthday with them in the Falcon Hotel here. It is therefore appropriate that this is where he has come to rest after living here for nearly 40 years.

What might also have been understandable would have been a different reaction to a changing Britain on his return from overseas. But no, he showed keen interest in new ideas and the younger generation and showed great generosity to them, without forgetting the educational standards of his own.

As a Godfather, he would check on my education regularly, and at one stage this involved writing on the anniversaries of military battles, in Latin. It was only when I stumbled on the idea of replying on the anniversaries of naval engagements, in Greek, that he declared he was happy with my education so far and we reverted to a more normal means of communication. It was this sort of repartee in correspondence or conversation, which he loved and at which he excelled, often spiced with humour.

He took great pleasure in introducing people to others he knew. He always had time for everyone and a pleasant word; many of us have enjoyed his hospitality and his anecdotes.

It was a mercy that he could carry on (albeit in a somewhat reduced capacity) much in this way right up to the end. He had always lived simply and modestly, and I know that his last few years at Buttsfield were comfortable happy ones. He much appreciated the care he received from the staff at Buttsfield, the Bromyard Hospital, and from relatives and friends who regularly visited him.

For someone so good at remembering others’ birthdays, it was sad that he missed his own 93rd by 1 hour and 40 minutes. But it was fitting, that for someone who was a wonderful Godfather, and had set an example to us all by his Christian faith, who had continued to read the lesson at the Old Church, Lower Sapey for as long as he could get there in SAM 8; that he took his Bible and prayer book in to hospital with him.

Which is why we celebrate his life today; -

For all that he means to all of us here with many happy

And fond memories of him,

For all that he has meant,

And for all that he always will mean to us,

Amen"

This tribute mentions the fact that Cameron was an intelligent, modest and generous man who cared very much for other peoples. He was a religious man and one who took a deep interest in young people and their proper education. He was also a practical joker with a "marvelous and mischievous sense of humour." All these things are mentioned in the tribute. One trait of John Ancrum Cameron that is not mentioned is that he was a brave soldier. Because Cameron chose not to speak of his military career and adventures in great depth, his Godson did not have knowledge of his behaviour in battle as uncovered by the author in this narrative account. Cameron had no medals to show the extent of his bravery; however, historical records of the 4th Indian Division and the Indian Sappers and Miners are replete with evidence of his actions. It is hoped that this work is a tribute to the bravery of a fine soldier.

ADDENDUM NO. 1

The following information regarding John Ancrum Cameron was kindly provided by Dr. David Gibbins via email after finding the author's website on the Internet:

David Gibbins was befriended by John Cameron in the mid-1970s when David was a boy living in Bromyard. They both shared a passion for King Richard III. John Cameron also fuelled David's fascination with colonial India at the time and was responsible for David's first ever pint of beer in a pub, at the age of 12!

David indicated that Cameron lived in rather reduced circumstances in a draughty garret in the centre of town. He had many friends of all types and was a cheerful eccentric. David's maternal grandparents, Tom and Martha Verrinder, lived only a few minutes' walk from Colonel Cameron's flat and could see his window from their back patio. They were both very solicitous of his well being during his last years and Mr. Verrinder often would return from his daily walk through the town with Colonel Cameron in tow and have him in for tea and cake, which he loved. David recalls many occasions when he sat in rapt attention with the two of them in front of his grandparents' house as they reminisced about military matters. Mr. Verrinder, who had been born in 1896, also was an old soldier who had seen plenty of action on the Western Front during the Great War of 1914-1918 where he served with the 9th Lancers.

David's grandparents are buried only a few yards from John Cameron's grave. His headstone is beautifully embellished with the crest of the Madras Sappers and Miners and his military rank is included on the headstone.

ADDENDUM NO. 2

The following are Colonel Cameron's notes for a lecture give at a social meeting some years after his return to the United Kingdom after serving 31 years abroad. In these notes he discusses his 8-month sojourn to various parts of the world. These notes were provided to the author by John C.W. Lyon in August 2004.

Mrs. Bertie-Roberts, Mrs. Hills, Ladies and Gentlemen -The Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports died in Walmer Castle on September 14th 1852 and the picture inspired by his death provides the title for this talk; for on September 28th 1956 I did my last day's work ever, and the next morning I started back to the United Kingdom after 31 years Eastern Service.

Michaelmas morning, ladies and gentlemen, and rather fun. Work behind me for evermore and all the lazy man's happy dreams of lifelong leisure; a day in a million; I wish I could convey to you my supreme contentment, almost my smugness as I left Kuala Lumpur Parish Church that Michaelmas morning and turned NOT right to the operations room but symbolically the opposite way, to Serembau, Singapore, Borneo, South India, Central Africa, The Canary Islands, and Home.

There is much I could tell you about Borneo, indeed there is much I would love to tell you about all the places I visited and the people I met in the 8 months of my slow journey home but I must limit myself to the highlights and in Borneo. I reckon the highlight was BRUNEI with its water village, the houses all on stilts, not just shacks but complete houses, with doors and windows that open and shut, easy chairs, pictures on the walls, birds in cages and pots of flowers hanging round the verandahs like the gardens of Babylon. There is no approach to these houses save by that; I toured the streets so to speak in a pinnace, and I happened to be outside the school when classes stopped at 1.15; the little Malay boys scampered out and each paddled off home in his own sampan like landbased boys ride off on their bicycles.

Back in Singapore, a friend just out of gaol asked me to lunch with him in the restaurant at the top of the newly-finished 16-storey Asia Insurance Building. As we lunched we wondered vaguely why people kept on going to the balconies and looking down and in the end we joined them and saw that the riots were taking place below. As a soldier, I have twice been at the receiving end of abuse and brickbats so this time it was nice to have a ringside seat and to notice how well the police were doing - the brickbat correctly caught on the wicker shield and the thrower smartly tapped with the baton. However the riots only lasted a few days and soon I was driving happily back to Malaya and up the East Coast. Let me tell you the difference between the East Coast and the West Coast; the West Coast is mostly mangrove swamp and modern civilisation, and is much visited and well travelled over, the East Coast is the beachcomber's paradise and is one long golden sandy shore lying between a Mediterranean blue sea and a belt of green coconut palms with pleasant little Malay kampongs at rare intervals; it is NOT, as it is sometimes mistakenly called, the real Malaya but it is quite delightfully the Malay Malaya.

On the East Coast therefore and not on the sophisticated West is the Beach of Passionate Love which 8 years ago when I first went there was extraordinarily well run by the rightful Sultan of Patani; but he died and it was taken over first by a drunken Hungarian pianist and secondly by a White Russian widow and with each change of ownership it slipped a little and then the monsoon took a hand and half of it slipped literally into the sea, and now it's rather forlorn but they do their best and still give you curried prawn omelets for breakfast and amusing things happen there , for instance a silver-tongued Malay spent a week impersonating me and being entertained by the sort of people who would be likely to entertain me; later I had to help him into an East Coast prison from where he wrote and asked me to meet him and take him home when he came out. I did so, and as his home was a long way away we stayed the night at a Rest House. Entering his Occupation in the book he wrote "Agriculture", and I suppose I looked mildly inquiring because he said "I been digging the prison garden". Well, yes, I too thought this awfully funny 'til I saw the signature of a genuine agricultural officer 3 lines higher up, so we spent a rather desperate evening staving off a genuine agricultural conversation.

Why I tell you all this is to show you that life on the East Coast is still happily carefree and unorganised.

One of the East Coast States is Trengganu and I stayed in its capital with a Malay Vet. The visit included Armistice Day, and on that day all the pigeon orchids flowered. A pigeon orchid is a miniature white orchid which resembles a very small pigeon in flight; about once a year all the pigeon orchids in the same area come out on the same day and for that only day only. I have seen them on 3 occasions - Armistice Day in Kuala Trengganu, the day of a big wedding in Seremban when the bride drove through an avenue of them to Church; and rather charmingly in Singapore on the Saints Day in 1949 on which the present Bishop of Singapore was being consecrated in London.

While on the subject of flowers, there is a very beautiful flower in Malaya which unfolds white in the morning and by evening has turned red: high-spirited hostesses pluck this flower on the mornings of their dinner-parties, and keep it all day in their refrigerator so that it stays white; they decorate their dinner table with it, and with the soup they draw some unsuspecting guest's attention it its pure white texture. "Yes indeed" says he "whiter than any lily". Wine is then served, and with the warmth of the room the flower begins to do its stuff, and with the savoury the guest's attention is again carelessly drawn to the flowers he earlier said looked whiter than any lily and his reaction is noted.

I made my way back into Central Malaya and revisited old friends and old haunts in Pahang. I once went up the River KECHAU to PETOLA, in a prahu from the main stream six days from the nearest town, which incidentally was where we once caught a mermaid on Christmas Day; sometimes we negotiated rapids and sometimes we got out and pushed and sometimes we got out and carried and twice we hauled our craft up a stone incline built by Sir Hugh Clifford last century and sometimes we just chugged but always we had our guns loaded and ready to shoot and finally we reached PETOLA and did our business and were fetched 2 days later by helicopter. The children of Petola have never seen a train or a motorcar or a bicycle or even a horse and carriage, they know only 2 forms of transport, the boat and the helicopter.

However, that has been a digression so now I must jump to Christmas in Kuala Lumpur where I went to a pantomime - Cinderella, and the Chinese youth who played the part of Buttons had a wonderful singing voice and in private life was a High Court Interpreter, doing 12 months for perjury; you see it was a Prison Pantomime and all the actors were serving sentences. Sitting next to me was an Indonesian who had only just ceased to be eligible to take 4. part and as each player came on he whispered biographical details. Cinderella, boy dressed as girl, was slim, handsome, almost ethereal looking and I couldn't believe she - or he - was an inmate until my neighbour said quietly "Armed Robbery 3 years".

KLUANG- I went to see the New Year in the Sergts. Mess of the Malayan Sapper Regiment I helped to raise; before that there was a cocktail party in the Officers Mess and as I knew every member of both Messes personally and had known some my whole time in Malaya a good evening was had by all.

I left KLUANG on New Year's Day and drove back up the Coast Road to Malacca, the same Coast Road I had driven down 18 months earlier on the night called TUJON LIKO the 3rd day before the big Muslim Feast of Hari Raya Puasa, as it were shall we say on Maundy Thursday. The road has a Malay house set back among the trees every 100 yards for 60 miles and on this one night in the year the paths leading up to each house are bright with little oil lamp-like nightlights: the belief is that an angel will come down that night from Heaven and will grant a wish to everyone he meets; the lights show the angel the way to your house.

I can't describe to you how lovely that night of TUJON LIKO was and what an impression it made on me; it was like driving through Fairyland.

I spent a night in Malacca. I loved Malacca, I used to go there as often as I could, generally staying with a retired policeman who lived among the coconut palms on the shore outside the town. I could dream about Malacca to you for days, it is the only place in Malaya with any real history and it has an atmosphere you find nowhere else. I had a clerk who came from Malacca, called Rashid Omar; he replaced a chap who had gone temporarily but not very honourably to prison and he used to travel to and from the office on rather a sparkling motor-bike; one morning I noticed it wasn't there nor Rashid either and I asked who not? "Tuan" I was told "Rashid had an accident and broke his leg and is in the hospital". "I am sorry" I said "how frightful, I'll go and see him this afternoon". "No need, Tuan" was the reply "he'll be back here by then". I said "he can't be, with a broken leg". "Tuan" was the devastating answer "one of his legs is a wooden one and that's the one he's broken".

Lastly Penang, correctly Prince of Wales's Island. I had embarked at Port Swettenham on Sunday January 6th and we called at Penang next morning. But on January 1st Her Majesty The Queen had raised George Town the island's capital to City status and 48 hours later the riots were in full swing: a curfew was imposed and order was being restored but the place looked uneasy. My father served in Penang some 70 years ago and loved it and was always so happy there and so have I been on my occasional visits; so it was sad to say "goodbye Malaya" to a Penang gaily decorated, festoons of colours along the roads, crests and coats of arms and loyal mottoes on all the big buildings, flags flying and flowers and illuminations everywhere, but the streets deserted except for security force patrols and a few people hurrying home to beat the curfew.

Revisiting India brings up very forcibly the question "Is it a mistake to go back?" And I reckon the answer is YES, unless you have as many people to see and as many places to go to as I did end you whiz round so quickly that you leave no time for nostalgia. Sunday evening is the trouble, not the Sunday you go to a strange Church but the Sunday you go to the Church just outside the lines, where the front pew still bears the plate "Royal Engineers" though the last Royal Engineer left 10 years ago and there are no more to come. But by tradition the senior R.E. officer attending Evensong reads the Lessons, and when I revealed myself to the Chaplain he asked me to revive the tradition - on that one Sunday night in 10 years, probably the last Sunday, ever.

I could see nothing wrong with the Army, I reckon they have about as high a reputation as they did when we left them. Nor with the Posts and Telegraphs who have faced up to corruption boldly; above every Post Office letter box is a large notice in English "Do not put air letters with adhesive stamps in this box. Take them inside and see them postmarked in your presence". In a place the size of Worcester a special clerk would do this and nothing else, holding your letters up afterwards so that you can see that the stamps are no longer worth licking off: in smaller places the Postmaster often invites you in and gives you a chair and a cigarette and perhaps a cup of coffee, and calls a clerk to postmark your letters while you sit and natter. I found 6. Postmasters invariably friendly and in MADURA they were holding Postal Courtesy week and the office and verandah were gay with coloured streamers; a willing guide came forward to take me round and show me the path of my letter from pillarbox to mailbag.

I went around lots of places in South India seeing old friends and familiar scenes and stayed a week in COORG and walked into the Fort in MERCARA and across its Bloody Tennis Court, laid out between the Rajah's Balcony and the Main Gate; prisoners to whom His Highness wished to show clemency were allowed to run across the tennis court while he shot at them from the balcony; if they reached the Gate alive they were free to leave but if not - well that's how the tennis court got its name.

Then down to the West Coast and its languorous backwaters where 40 years ago a short leave used to be so lovely; and even only 20 years ago I spent a Christmas morning drinking champagne with M. 1'Administratem of the French territory MAHE; he was a dear and so was his successor whom I stayed a night with at the end of the war. I noticed he had no radio and I knew there was no local paper in French and he spoke no English so I asked him he learned of great events; he explained "I can read simple English words in capital letters so I take in the Madras Mail and spell out the headlines; if it sounds exciting I take the whole paper down to the Postmaster who understands English and translated it to me".

I revisited CAPE COMORIN where you can watch the sun rise and set in the sea; indeed I could talk about South India to you all night but I'm going to limit myself to reeling off a few place names and if any listener has a particular interest in some place I went to and would like to hear more I'll be delighted to tell all I know when this Talk is over. The places I went to, in addition to those I've already mentioned, are:-MADRES - WANDIWASH - PONDICHERRY - VELLORE - BANGALORE - SERINGAPATAM - MYSORE - VIRAJPET - POLLIBETTA - SULTAN'S BATTERY - OOTY and THE NILGIRIS - MADURA - TINNEVELLY - NAGERCOIL - TRIVANDRUM and a Tea Estate at KALLAR BRIDGE - POONA - KIRKEE - BOMBAY, and in PAKISTAN a day in KIAMARI and KARACHI.

Two incidents stand out in my memory, from Bangalore, the first one made me feel my age, the 2nd one was just nostalgic. My first tour in India we used to play hockey against a local team 7. called the Bangalore Indians whose centre half was a young law student called Kosal Ram, a nice lad and a first-class hockey player. I went away and he went away and we met again this year when he came to tea with me for auld lang syne; I suppose it was stupid of me still to think of him as the active young law student of the twenties, for he walked in greyheaded and venerable - he's now a Retired Judge.

The second incident took me back to the birth on February 17th 1938 of a son to the wife of one of my best n.c.o's, February 17th is the anniversary of the Battle of Meeanee and as the Company we were both then in had played a notable part in that battle we laughingly called the boy Meeaneesami. In February of this year the father now a pensioner, came to see me and as you will have guessed brought with him Meeaneesami, 19 years old and a freshman at a University and we had an affecting re-union; but what neither you nor I could have guessed was that the father carried a brown paper parcel and unwrapped it and showed me, carefully laundered and folded, the little shirt and shorts in our company colours which I had had made for Meeaneesami then aged 2 when I left for the war in 1940.

Incidentally, it was this boy's father who won my best garden prize in a never-to-be-forgotten competition over 25 years ago. Each recruit squad had its strip of garden outside its barrack block and I offered a prize for the best garden on a certain Sunday morning some weeks ahead when I would come and judge. Well, some squads were keen and some were idle but Judgment Day came round and one hitherto idle garden was seen to be a blaze of flowers - quite genuine flowers and truly growing and not merely wired onto wooden stalks. So Meeaneesami's father and his squad got my prize though I gave it with some misgivings, to be fully justified next morning when both the C. of E. and the R.C. chaplains lined up outside my office to complain of wholesale depredations from both their cemeteries and a pack of my recruits suspected.

My only other Tiger Story deals with my passage through the Customs when I left Bombay; in my 2 days there I had been particularly well looked after by a former Madras Sapper n.c.o. now a traveller for cement, and as we approached what was clearly going to be a very stiff Customs examination he said "Stick by me. Sahib, stick by me; don't let anyone, ANYONE, take you away". Well, sure enough all sorts of junior and senior officials, seeing my white face, rolled up and offered their services to be quite clearly at a price, but I stuck by my pal and finally we reached the counter he had been making for and I was introduced to the examiner "you remember Cameron Sahib who used to play hockey for 10 Company?" and we were off reminiscing and I was so nice and agreeable and after exchanging old friend news he apologized and said "well look, you won't mind my just chalking your bags and sending you on your way will you? And do come back to India and see us again". It was only when I later heard my fellow-passengers saying to each other "You got away with 20 rupees; I had to give that to the head man alone" that I realized what a dividend the hockey matches of a quarter of a century ago were now paying.

We were only a few hours in Pakistan; the Pakistanis were smiling and courteous and friendly but Karachi looks a bit ravished and in need of a coat of paint; Keamari its harbour has expanded out of all recognition since I was stationed in SIND 22 years ago.

From Karachi we sailed down the Indian Ocean, bumped gently over the Equator, and put in at Mombasa where we spent 3 days swimming and sightseeing.

I liked Mombasa but even more I liked Zanzibar which bore a nostalgic resemblance to my much-loved Malacca. Zanzibar Cathedral is most impressive with its clock which keeps Islamic time (as do all the Zanzibar public clocks except the Post Office) as a tribute to His Highness the Sultan who gave it - gave it? or should we say donated it? I called on H.H. and was accorded a courteous bow and a charming smile, and an Arabic greeting; he is a GOOD Ruler, much loved by his subjects.

There are many Livingstone relics including his house and the room where his body lay after its 1000-mile journey from Lake Tanganyika; the streets of Zanzibar are narrow and fascinating, reminding me occasionally of Kirkwall and Stromness in Orkney; and twice I drove with friends through the clove orchards to bathe in clear sea off sandy beaches.

If I have left my heart in Malaya I fancy it has engraved on it MALACCA; if I had lived long in Africa I feel the word would be ZANZIBAR; of the 7 African territories I went to I liked Zanzibar the best, and a close runner-up would be Tanganyika whose old German capital DAR-ES-SALAAM we fly to now.

The best thing about Dar-es-Salaam is its pleasant sounding name, the next best its picturesque harbour approach. The old German Government House now the British Govt. house is large and imposing but no other building impressed me except the old German railway station; the roads all seem to have been laid out at right angles, the name of the principal street is ACACIA AVENUE. Well, I ask you.

From Dar-es-Salaam I went by bus to MOSHI near Mt. Kilimanjaro, in fact I crossed the whole of British East Africa by bus, from the Coast to the Belgian border, over 1500 miles for under 10 guineas. I know no African language but no men could have been kinder or more helpful than the three members of that Tanganyika bus crew none of whom spoke any English. They drove me right up to the places they thought I ought to eat at, a Greek restaurant for lunch, an Indian cafe for tea, and a slap-up European hotel for dinner, and in between they bought me bananas. At 3 a.m. we reached my destination, the Livingstone Hotel in MOSHI, the driver leaped out and carried my bags in, woke up all 3 night watchmen, explained who I was, and waved a smiling goodbye. The watchmen were all over me too: it seemed no room had been specifically reserved so they gave me halfadozen keys and said "Choose which room you like best, Bwana," which I did and chose lucky for 3 hours later I woke to see from my window MT. KILIMANJARO free of cloud and in all its snow-covered glory. It is an unforgettable sight, even after only a short 2-day stay it made an immense impression on me, I'm not surprised to learn that it "gets" you completely if you live and work beneath it.

Next day I crossed into Kenya and I'm not talking much about Kenya because you've already heard of the adventures there of Karina Smalley and Pauline Peacock both nees Lyon; but I don't suppose those adventures included a night with an alarmingly tough Brigadier at Thomson's Falls 7700 ft. up, 7700 mark you, and he had no electric heating and used his fireplaces solely to keep his radio batteries in.

Also I enjoyed visiting a Nanyuki hotel where a silver line is let diagonally into the top of the bar and marks the Equator. Also the happily-named Equator railway station also crossed by the Equator where I witnessed the affectionate meeting of a husband and wife across the hemispheres. This railway station has a Post Office where your letters will be postmarked rather majestically EQUATOR KENYA. Also RUMURUTI where a Captain CARR HARTLEY has a license to capture and keep live animals and subsequently sell them to the world's zoos. I'm told my views on Kenya's game reserves are sheer heresy but I had the wretched beasts and their parks so dinned into me as a MUST that I jibbed at visiting all except one which my kind hostess drove me into near Nairobi and we were sniffed at close-at-hand by a hungry-looking Lioness with a gleam in her eye. At RUMURUTI without effort I saw lion -leopard - cheetah - hippo - giraffe - baboon - chimpanzee - ostrich -warthog - hartebeeste - hyena - vulture - snake - secretary bird -crowned crane - and Thomson's gazelle but NOT the rhinoceros who was stated to be out for a walk.

Easter I spent in Kampala, Easter Monday I set off for the Congo teaming up with an American Colonel. We stopped 2 days in the glorious scenery of KABALE and left next morning in a wholly African bus for RUANDA: our fellow travellers were African Protestant schoolchildren going home for the holidays and they sang melodiously and in harmony the better known English Protestant hymns. Uganda isn't Arkansas but eyebrows were nevertheless slightly raised at 30 young blacks and 2 elderly whites singing as they journeyed Jerusalem the Golden.

Once across the Belgian border the cost of living rockets; no more buses at a penny a mile, from the frontier to LAKE KIVU it was a shilling a mile for each of us and we both agreed that the happy laughing singing companionship of our East African bus-travellers had been very poorly replaced by the stately and expensive company of each other. However just around LAKE KIVU I didn't frightfully grudge this for the scenery really was magnificent and that night we saw 3 active volcanoes glowing and spouting round our hotel.

Whatever Belgian advertisements and propaganda may say I personally reckon they do NOT want tourists unless such tourists are so rich that they bring their own cars or will hire the local ones, or so rushed that they go everywhere by air. I am quite sure that they don't want the mooch-along poor-white type of tourist like me; but that isn't to say that individual Belgians didn't welcome me for they most certainly did, and I received great kindness at the hands of all I met and generous hospitality, but it's not a country for a man without a well stocked wallet.

I went by slow steamer down Lake Kivu, stayed a night in Bukavu and next day boarded the Lake Tanganyika steamer at its Congo port of KALUNDI from where it was 2 hours to USUMBURA on the eastern shore and where my American colleague left me to return to Kenya. He was replaced by 2 tali Missionaries.

All that night and next morning we steamed slowly down Lake Tanganyika, second deepest lake in the world, the deepest being Lake Baikal, and I improved my French talking to the 2 missionaries who spoke it carefully and clearly. The Lake is narrow, you can see both shores at once, craggy and inhospitable they look from a distance but are surprisingly green close to, even though no-one lives there.

We spent a still hot Saturday afternoon at Kigoma, the sad little Belgian-built terminus of the old German railway from Dar-es-Salaam and here I had a memorable adventure: I accidentally came across a sophisticated young mulatto from the French colony of Reunion and an elderly Indian engine-driver waiting to take the night Mail to the Coast. We sat round a rickety bamboo table on the verandah of Kigoma's lonely one-horse hotel and we talked and we drank cold beer and I felt myself developing more and more into a Somerset Maugham story and wondering if I should come to the same inconclusive end. No-one except the last waiter came near us and the sun began to set over the Lake and the steamer hooted and I had to go. Many memories of my journey home will fade but not that one - the Lake and the sunshine and the stillness and the mulatto and the engine-driver and the beer and the sad-looking waiter and the tumbledown verandah on that hot Saturday afternoon by the shore of Lake Tanganyika.

Next morning we berthed at Albertville and I said goodbye to the missionaries; did I hear one of them say something to the other in English? I asked "Vous parley anglais mon cure?" "Yes SIR" said he "we are Americans".

From Albertville one takes the train to Elisabethville, chief town of the Southern Congo including the copper area; the journey lasts 48 hours, you cross the wide and swampy and quite unromantic Congo River on a bridge, built last year and all except the last 4 hours of your journey which are on a different railway system are spent - shades of Stanley and Livingstone and my Naval name-sake; - in an airconditioned wagon-lit;

The Southern and Western Congo country is interesting but no where spectacular: I enjoyed my 2 days in the wagon-lit and my following 4 days in EVILLE where I was introduced to two Clubs one Royal and sedate, the other openair swimming and very modern; but I hadn't crossed 3/4 of Africa to linger in a town and on the Saturday I set off for Portuguese West properly called Angola. You know as soon as you've crossed the frontier because your bill for lunch looks like it was just for elevenses, the Portuguese prices are some 30 to 40 below the Belgian. And I thought the Benguela Railway one of the best I had travelled on, with its comfortable carriages and admirable restaurant car and its sensational descent the last morning from 5000 ft. a.s.l. to 0 - it is the only railway where I have been able to take a photograph of my own engine going round a hairpin bend ahead of my compartment.

Why did I go to Angola? Heredity I suppose for my great grandfather commanded a Portuguese Division in the Peninsular War and held a high opinion of the Portuguese as fighting soldiers when competently led. Twice in India I visited GOA and the memories of my days there are among my happiest. Do I speak Portuguese? No, but on the West of India Portuguese Railway I was intrigued by the notices describing the Gentlemen's Waiting Rooms - "Salla da espera para caballeros" or literally "Hall of hope for Cavaliers".